As conventional thinking goes, the 1970s, and this moment in particular, marked the beginning of America’s so-called “War on Drugs.” It’s a war the United States continues to wage to this day, contributing to a grossly overcrowded prison system — 450,000 are currently incarcerated for drug offenses, up from 40,000 in 1980 — and footed by more than $1 trillion in taxpayer funds. Even today, as the Trump administration moves ever-closer to reinvigorating this open-ended crusade, it’s Nixon who is disproportionately credited with having fathered this perpetual battle.

Yet it’s disingenuous to label Nixon the mastermind of the anti-drug movement, just as it would be ignorant to consider the drug war a modern-day phenomenon. The dubious distinction of America’s first drug czar belongs to a man few know anything about: a career government official named Harry Anslinger, who had taken over the Bureau of Prohibition just as the ill-fated ban on booze was ending. To get a more precise understanding of the machinations of Anslinger’s anti-drug blitzkrieg, one must only become acquainted with his bizarre statements on the correlation between drugs and minorities.

“There are 100,000 total marijuana smokers in the U.S., and most are Negroes, Hispanics, Filipinos and entertainers,” he once said. “Their Satanic music, Jazz and Swing result from marijuana use. This marijuana causes white women to seek sexual relations with Negroes, entertainers and any others.

“Reefer,” he declared on another occasion, “makes darkies think they’re as good as white men.”

The meaning is clear: African Americans and other minorities under the influence of marijuana were a danger to the white race — women, especially.

“It’s important to understand: [Anslinger] was regarded as a crazy racist in the 1920s. You have to be super-racist to be regarded as racist then,” Johann Hari, author of the definitive book on America’s drug war, “Chasing the Scream: The First and Last Days of the War on Drugs,” tells News Beat. “He used the ‘N’ word so often in official government memos that his own senator said that he should have to resign…and the other group that he really hated were people with addiction problems — addicts.”

“He had this bad experience when he was a kid growing up in rural Pennsylvania with an addict who lived near him, and he believed addicts were like lepers,” Hari explains. “They had to be quarantined, they had to be cut off from the rest of society, or they would spread. They were contagious.”

BackBeat: LISTEN TO THE NEWS BEAT TEAM DISCUSS THE MAKING OF THIS EPISODE

Anslinger was the first-ever commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN), the predecessor to today’s Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). Although he served nearly as long as the FBI’s J. Edgar Hoover — a remarkably prolific run from 1930 to 1962 — his role in shaping law enforcement policy nationally and globally has been overshadowed by Nixon and Reagan’s much-publicized and equally egregious anti-drug campaigns.

Nancy Reagan’s “Just Say No” slogan is ingrained into our psyche, while Anslinger’s deranged proclamations — “Negro entertainers with their Jazz and Swing music are declared an outgrowth of marijuana use which possesses white women to tap their feet,” for instance, or “Marijuana leads to pacifism and Communist brainwashing” — are resigned to the internet scrapheap, almost exclusively taking up real estate on innocuous websites.

It’s near-impossible to exaggerate Anslinger’s contributions to the now-global drug war. Not only did he have an over-sized role in promoting and enforcing anti-drug policies and lobbying for stricter laws in the United States, Anslinger successfully strong-armed entire countries to wage this war, his way. To best illustrate Anslinger’s intimidation tactics, Mexico, for example, initially refused to comply with his demands until the United States threatened to withhold painkillers from Mexicans, according to Hari.

As Hari documents: A Mexican doctor named Leopoldo Salazar Viniegra, who treated drug addicts, cited findings from his own study detailing how some of the apparent dangers of marijuana was exaggerated. Instead of blindly following the United States into a brutal drug war, he suggested the Mexican government keep drugs legal, which would allow officials to regulate and control its sale.

“This would prevent criminals from controlling the trade and so, end drug trafficking and the violence and chaos it causes,” Hari writes.

For Anslinger, this was all meant to ensure the FBN’s survival. And what better way to promote this new war than inciting fear of the “others,” mainly African Americans, Mexicans, and even Jazz musicians, to drum up support for this offensive. Since Congress had already banned heroin and cocaine in 1914, Anslinger directed resources at marijuana, a drug he once claimed would cause Frankenstein to shake in his boots and deemed “the most dangerous drug in the history of mankind.”

So committed was Anslinger to this undertaking that he eschewed logic and scientific reasoning. Such was his state of mind, that when more than two-dozen scientists advised that weed was not a “significantly dangerous drug,” according to Hari’s book, he followed the recommendation of the lone doctor who reaffirmed his bias. Anslinger fought this war both on American streets and through the airwaves, using dubious claims to justify the FBN’s actions. Anslinger’s war had a lot to do with stamping out what he perceived to be a decaying social fabric, hastened by a supposedly diabolical drug. He especially viewed Jazz culture, combined with cannabis, as a distinct threat.

“Jazz was the opposite of everything Harry Anslinger believed in,” Hari writes in his book. “It is improvised, and relaxed, and free-form. It follows its own rhythm. Worst of all, it is a mongrel music made up of European, Caribbean, and African echoes, all mating on American shores. To Anslinger, this was musical anarchy, and evidence of a recurrence of the primitive impulses that lurk in black people, waiting to emerge.”

“Anslinger’s agents reported back to him that ‘many among the jazzmen think they are playing magnificently when under the influence of marijuana but they are actually becoming hopelessly confused and playing horribly,’” he adds.

For Hari, the modern-day drug war started 78 years ago, when the legendary Jazz singer Billie Holiday performed “Strange Fruit” before a mostly white audience in Manhattan, in 1939.

“The song describes the bodies of African American men hanging from trees in the South, and she describes that as the ‘Strange Fruit of the South,’” he explains. “And that night, Billie Holiday received a warning from the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, who were the federal agency in charge of enforcing the drug laws. And they basically said: ‘Stop singing this song…’ If you want to understand where the War on Drugs begins and why it continues, I think this moment in American history is really important.”

Anslinger’s grievances with Jazz intersected with his job as the nation’s chief drug officer. After discovering that Holiday was using heroin, he directed one of his agents to spy on her, according to Hari. The war was on, and it didn’t take long for Anslinger to find his footing.

“He was unusually gifted at channeling the fears and hysterias of American society at that time and projecting them onto these inert chemicals: onto cannabis, onto cocaine, onto heroin,” Hari says.

“It’s easy to forget this now, but drugs were legal in most of the world when Harry Anslinger arrives in office, and cannabis was legal in the United States,” he continues. “Anslinger has promised that once you ban these drugs, they’ll disappear, they’ll be got rid of, your addiction will be a distant memory.

“Now, of course, the drugs don’t disappear, obviously, so Anslinger needs to invent a new reason why this has happened, and he says ‘Well it’s the Latinos, it’s the Mexicans, it’s Latin America, and the Chinese. They are flooding our country with drugs,’” Hari adds. “In fact, he said, ‘They’re doing it as part of an orchestrated communist conspiracy to weaken the United States…’ And he particularly says in words that are uncannily similar to what Donald Trump and [Attorney General] Jeff Sessions say now, that the United States has a drug problem because of Latinos flooding the country with drugs.”

Maia Szalavitz, a former addict who writes about addiction, among other topics, for a number of news outlets, explains how bigoted fear of minority groups helped forge America’s drug policy.

“The history of our drug laws is a history of racist panics,” she says. “We get cocaine illegalized because people believe it makes black people impervious to bullets — like, if only, right? And they believe it makes black men rape white women or want to seduce white women, and we get the first opioid laws that are criminalizing when the Chinese railroad workers — ‘Oh they’re going to use this drug to seduce or rape white women.’ And you get the marijuana laws, and it’s like Mexicans and Jazz musicians, ‘They’re going to sleep with white women, and this is going to be a problem.’

“It’s all about fear of people taking white women,” Szalavitz continues. “It sounds ludicrous, but you read this stuff and you’re like ‘Wow, people created these panics based on absolutely no facts…. This is a history of bias and of animus against certain groups of people. Even alcohol prohibition, this was about fear of immigration and these immigrants are bringing this bad stuff with them and they’re taking our women…. You know, it’s just the same stuff over and over again, it’s never actually about how harmful this drug is.

“And this is part of the Southern Strategy,” she explains further. “The Southern Strategy is this Republican idea that we can win over these racist Democrats by appealing to their racism, and we can get the South if we just sort of covertly say things like ‘inner-city crime’ and ‘evil hippies,’ and we can get those voters over to our side by cracking down on crime — and that’s a code for cracking down on people of color.

“We’re doing this crackdown, you’ve got all these images of black people rioting, this kind of stuff, and it’s just used as a way to criminalize these populations,” adds Szalavitz. “As [author] Michelle Alexander writes, it’s ‘The New Jim Crow,’ it was not overtly targeted at those communities…and that was deliberate…then when President Reagan comes into office, you have the second big wave of this drug war.”

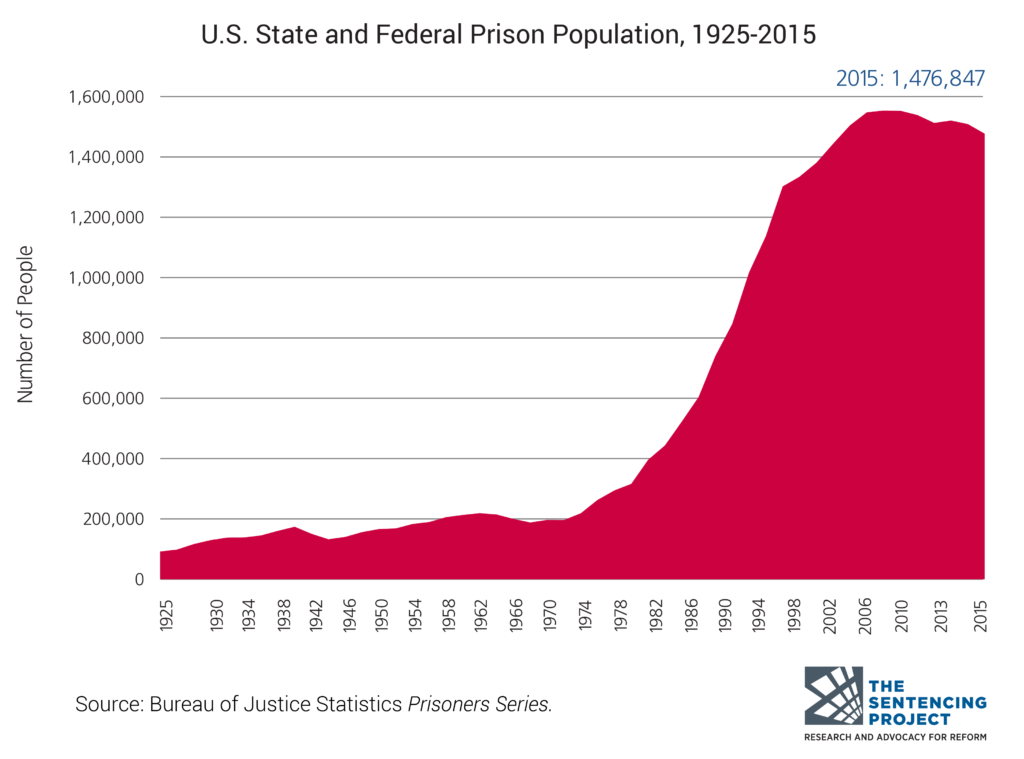

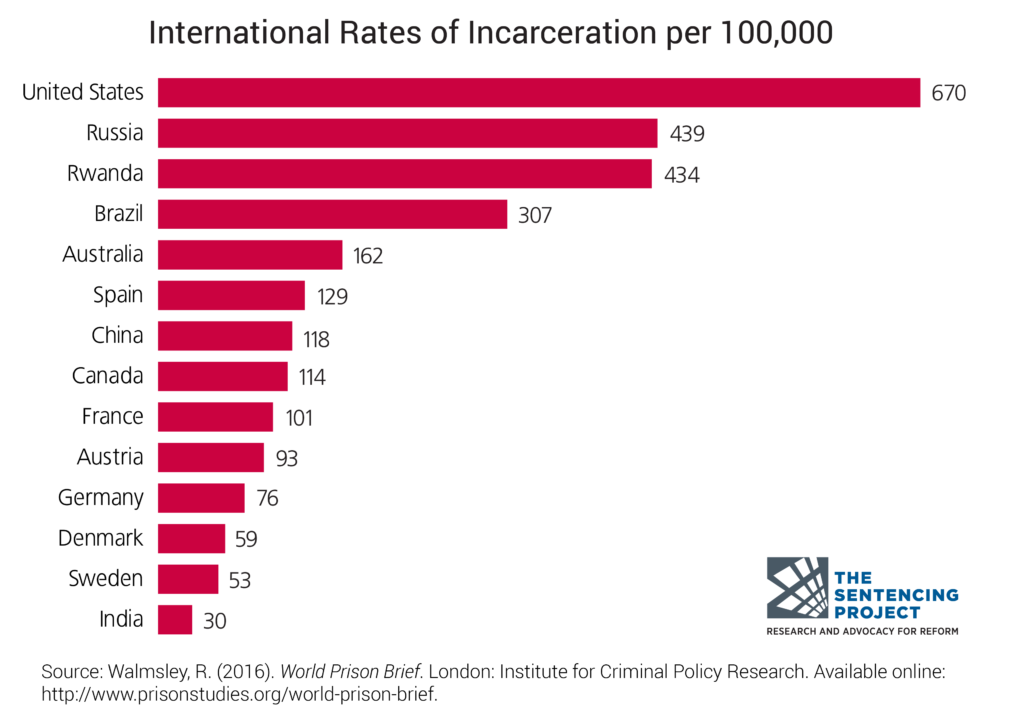

The true origins of the United States-led War on Drugs is important to understand in order to fully comprehend how we ended up where we are today. Currently, the United States accounts for approximately 5 percent of the global population, but 20 percent of the prison inmate population worldwide. The number of U.S. citizens jailed on drug offense in 1980 was 40,900; by 2015 that number soared to 469,545, according to The Sentencing Project, a nonprofit that advocates for criminal justice reform. The Bureau of Prisons reports that drug offenders account for 46 percent of the federal prison population.

This war Anslinger started has been at the centerpiece of American anti-crime policies for decades.

History has thoroughly documented Nixon’s war and Reagan’s escalation, but only until recently has President Bill Clinton’s 1994 crime bill come under intense scrutiny for establishing mandatory minimums for drug offenders. Nearly two decades after the crime bill was enacted, 36 percent of federal drug convicts received mandatory minimum sentences.

“I think the War on Drugs is a huge part of mass incarceration; it’s one of the reasons why we had this ballooning in the ’70s, why we continued growing the prison population in the ’80s under Reagan, and why it grew even further under Clinton,” Alex Clermont, a writer and prison reform activist, tells News Beat. “It is the War on Drugs. It’s used as an excuse to fund police departments, it’s used an excuse to lavish attention on individuals who are able to stir up law and order rhetoric in their campaigns. So it is a main reason why the prison population is as big as it is in the United States. So I think there’s a direct connection: The War on Drugs has created the boom of prison population.”

If the goal of the drug war was to imprison people for drug offenses, however minor, than the campaign has been devastatingly effective. But at what cost? The near-century-old tough-on-crime approach has done little to prevent drug use among Americans. According to the United Nations, the United States leads the world in illicit drug use and overdose deaths, which claimed more than 50,000 Americans in 2015, accounting for more fatalities than car crashes.

As Hari traveled across America, and other countries impacted by this never-ending drug war, it was hard to divorce today’s anti-drug initiatives with Anslinger’s offensive — from a prison camp in Arizona to a crime-ridden neighborhood in Brooklyn and the streets of Ciudad Juarez, a particularly violent Mexican city abutting the southern border. He sees it in the policies pursued by every presidential administration since Anslinger became America’s most intractable and longest-serving drug czar.

“Every U.S. president since Harry Anslinger has fought his war,” Hari says. “Of course, Nixon is a very Anslinger figure — paranoid, racist, and so on — and of course, we see this with Reagan. Actually a guy who doesn’t get enough stick for this is Bill Clinton. The worst person on the drug war — Nixon is a monster, Reagan is a monster — but actually Bill Clinton is responsible for some of the worst intensifications of the drug war, some of the most racist policies. So this has been a bipartisan affair.”

If Billie Holiday were singing today, it’d be difficult not to imagine her crooning about the black bodies locked away in America’s prisons, just as she bellowed about black men hanging from trees in the South all those years ago.

Anslinger and Holiday are long gone, but the war that consumed their lives—in Holiday’s case, irreparably—is alive and well.