The procession of activists sauntered along the Pennsylvania Avenue perimeter of Lafayette Square, across the street, their orange jumpsuits even more striking against the White House backdrop. Nearby, spoken word artists began to sing.

“Muslim brothers, you do not walk alone…we will walk with you…and sing your spirit home…”

“We’re gonna build a nation, that don’t torture no one…but it’s gonna take courage for that change to come…”

Some of those shrouded held signs blaring “41”—the number of people still detained at the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base in Cuba.

A handful of U.S. Secret Service officers looked on from the center of the street—Pennsylvania Avenue ominously cordoned off by yellow police tape. Their faces betrayed little intrigue, as if they had all seen this play out before.

The nagging question about what to do with the remaining detainees and how to finally shutter a prison that internationally is viewed as a permanent stain on the United States’ human rights record has emerged as one of the most stubborn issues of our time.

Two previous presidents acknowledged the need to close the prison camp, also known as Gitmo—a position the Trump White House recently undercut.

Sixteen years since the prison first opened its gates to so-called “enemy combatants” with legally ambiguous protections, most of the more than 750 formerly imprisoned there have been released. Still, 41 men remain marooned on the Cuban island, which the U.S. government leases, and as many as five have been approved for release by a collection of government agencies.

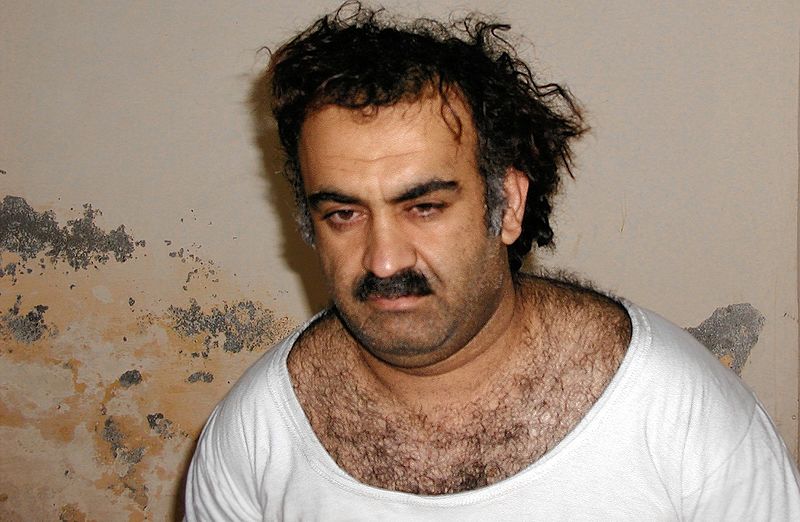

They range from the infamous mastermind of the Sept. 11 attacks, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, to men who had been tortured at CIA black sites and never charged with a crime. Upwards of nine detainees have died there, some by suicide, and others on hunger strike are reportedly in poor health. The oldest man at Guantanamo is now 70 years old. Others suffer from psychological torture brought on by their indefinite detention.

Guantanamo is for all intents and purposes a Muslim prison. Most of the prisoners there were sold for bounties, or picked up on the battlefield in Afghanistan.

The facility formally reopened on Jan. 11, 2002. Three months later, the U.S. Attorney General approved about a dozen interrogation techniques that amounted to torture, including waterboarding. The methods mostly played out at CIA black sites: windowless rooms where suspected terrorists were waterboarded, slammed into walls, threatened with confinement in wooden boxes resembling coffins, rectally fed, and/or deprived of sleep.

Among the men rendered to Guantanamo was Abu Zubaydah, a suspected leader of al Qaeda, who was captured in Pakistan in 2002 following an intense firefight. Although U.S. officials have acknowledged that Zubaydah was not the prized captive they initially believed, he is still being held at Guantanamo without charge, and there’s been no indication he’ll ever be released.

Zubaydah, perhaps more than any other detainee, represented the clashing perspectives inside the government following the attacks. In an interview with the FBI shortly after he was captured, Zubaydah confirmed Khalid Sheikh Mohammed was the mastermind of 9/11. He had also expressed a desire to cooperate with the bureau’s special agents.

Then the CIA stepped in.

Forty-one demonstrators marched throughout Lafayette Square, across the street from the White House, on Jan. 11, 2018 ,to protest the indefinite detention of dozens of men at Guantanamo Bay prison in Cuba. (News Beat Podcast)

Zubaydah was transferred to a black site where he became the first terror suspect to be waterboarded. The CIA wanted “actionable intelligence” on impending attacks they could thwart, but Zubaydah gave up no such information during 19 consecutive days of torture, according to the Senate Intelligence Committee’s so-called Torture Report.

The FBI objected to Zubaydah’s CIA captivity, noting that he was offering “throw away information” and “holding back from providing threat information,” according to the Senate report.

An FBI agent quoted in the Senate report stated the CIA methods were “quite odd,” because all the information previously obtained from Zubaydah had come from the FBI.

The 2014 report was scathing in its rebuke of the Bush-era torture program, concluding it was ineffective, deeply flawed and “far more brutal” than even members of Congress were led to believe. Human rights groups have said the torture methods used violated the Convention Against Torture, which was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in December 1984 and signed by the Reagan administration in 1988. Some of those tortured in secret black sites were transported to Guantanamo where they’d ostensibly face prosecution.

One of President Obama’s first acts of office following his inauguration in 2009 was signing an executive order calling for Guantanamo to be shuttered, a promise he was unable to fulfill.

Trump fired back recently with his own executive order that reverses the Obama-era plan to close the prison.

Attorneys for the remaining detainees worry that the men still at the prison, even those who have been cleared for release, will remain there as long as Trump is president.

In a sprawling legal filing, a coalition of rights groups requested that a federal judge intervene on behalf of 11 men who have not been charged yet have remained imprisoned for 10 to 16 years, respectively.

That these men are still imprisoned despite having never received a legal reason for their detention violates the Constitution and the 2001 Authorization for use of Military Force, which was enacted in the days after the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks, they argue.

The petition notes that while Presidents Bush and Obama combined to release more than 700 detainees (532 alone under Bush), the current administration has demonstrated little desire to release any of the 41 remaining prisoners. This creates a legally untenable situation, they argue: detention for detention’s sake.

“We’d ended up with a bunch of guys warlords had turned in for a bounty with no evidence they had any value,” Fallon continues. “We called them dirt farmers—lots and lots of dirt farmers.”

—Mark Fallon, former DoD official and author of “Unjustifiable Means: The Inside Story of How the CIA, Pentagon, and U.S. Government conspired to Torture”

Indeed, Trump has vowed to load GITMO with many more “bad dudes.” Trump’s decision to nix Obama’s plans to close the prison was met with rapturous applause from his Republican cohorts during his first State of the Union Address.

That Republicans in Congress nearly unanimously disapprove of shuttering Guantanamo is a stunning reversal from a decade prior, when previous GOP heavyweights President Bush and Sen. John McCain (R-AZ), then a presidential candidate, indicated they’d prefer to see it closed.

But the politics governing Guantanamo changed dramatically with Obama’s election. Among the steps he took to resolve the detention of the remaining detainees left over from the Bush administration was a task force consisting of six federal agencies, including the Department of Defense and Joint Chiefs of Staff. The board was charged with conducting a comprehensive review of each detainee at the prison and providing recommendations.

At the outset, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld said only the “worst of the worst” would be taken to Guantanamo, a talking point still used by the prison’s staunchest defenders.

If the most recent legal challenge is unsuccessful, Guantanamo could inevitably become what its critics fear the most: a legal black hole. To some, Gitmo is already a place where suspected militants go to never be seen again.

BOUNTY HUNTERS

When Guantanamo reopened in 2002, the Bush administration intended it to be a temporary facility that would be used to hold prisoners and “exploit” them for intelligence, according to Mark Fallon, a former Department of Defense official who was part of the first-ever task force charged with investigating terrorists for possible military commissions.

Sixteen years and counting, the prison camp is still active, at a cost of more than $440 million per year—$10.7 million per detainee.

Stocking the prison with hundreds of recently labeled “enemy combatants” was a stark departure from when the camp was mostly used to house Haitian and Cuban refugees, but the island still had “primitive” facilities, Fallon explained in an interview with News Beat Podcast outside the White House, recalling his time there in the 1990s.

“They would look like a dog kennel,” he said of the facilities. “There were cyclone fences with two buckets, one for drinking, one for human waste, and it was supposed to be a temporary facility. And it was just meant somewhere to hold them until they can build another place and they did and they moved.”

Fallon returned to Guantanamo in 2002 as a member of the DoD’s Criminal Investigations Task Force (CITF). Almost immediately, competing interests emerged: trained investigators in his task force seeking to learn the truth through legal methods, and others who believed more aggressive measures were required.

U.S. Secret Service police keep watch of a Guantanamo Bay protest outside the White House on Jan. 11, 2018. (News Beat Podcast)

Fallon had made a career of scrutinizing high-profile attacks, including as Tactical Commander for the the USS Cole task force.

In his new book, “Unjustifiable Means: The Inside Story of How the CIA, Pentagon and U.S. Government Conspired to Torture,” Fallon notes the abrupt change in U.S. policy toward federal terror investigations, which previously were the responsibility of federal agents.

What stood out in Bush’s order on November 2001 advising that the DoD would take the lead on Gitmo probes, Fallon writes, was how ambiguous it was. Anyone whom the president had “reason to believe” had an affiliation with al Qaeda, for example, would be subject to detention.

“Most of the people who ended up at Gitmo were picked up by the Northern Alliance or other groups that didn’t necessarily have any interest in the global war on terror, aside from picking up a $5,000 per head bounty,” Fallon writes.

The detainees taken to Guantanamo on bounties represented an astonishing 86 percent of all the people who eventually ended up at the prison, according to Reprieve, an international human rights group. These were people who were paid for by the U.S. government, the result of American planes flying over Afghanistan and Pakistan dropping leaflets offering thousands of U.S. dollars for “suspicious” persons.

Fallon, in his book, viewed the entire process by which incoming detainees were scrutinized as “simply nonfunctional.”

He writes that being in possession of a rifle or “visiting a guesthouse where al Qaeda operatives were thought to have stayed could be interpreted as someone aiding and abetting the enemy.” This also includes, he continues, people held at gunpoint and forced to join the terror group’s ranks.

“It got even more ridiculous,” Fallon writes. “Because some terrorists had used an internationally popular model of Casio digital wristwatch as a time for bombs, wearing one of these watches became suspect…and not just suspect: there were actually detainees held at Gitmo because they had been wearing a Casio watch.”

“We’d ended up with a bunch of guys warlords had turned in for a bounty with no evidence they had any value,” Fallon continues. “We called them dirt farmers—lots and lots of dirt farmers.”

On several occasions, Bush had advocated for the prison to be closed, but eventually decided to keep it open. Even still, Bush has referred to Gitmo as a “propaganda tool” for the country’s enemies. Militants abroad have reportedly used the prison as a rallying cry, and westerners captured by the death cult known as ISIS have been outfitted with orange jumpsuits and subsequently beheaded on camera.

While Bush was considering what to do with Guantanamo, the two men vying to replace him, McCain and Obama, had pledged on the campaign trail to do away with the prison. Obama in his second day in office signed the executive order that laid the groundwork for its closure. But Obama met significant resistance from Congress, as well as countries from which some of the detainees resided.

“It’s illegal and it’s been illegal ever since its inception. It was designed to be a prison outside of the law and there is no such thing and there should be no such thing.”

—Shelby Sullivan-Bennis, staff attorney at nonprofit Reprieve

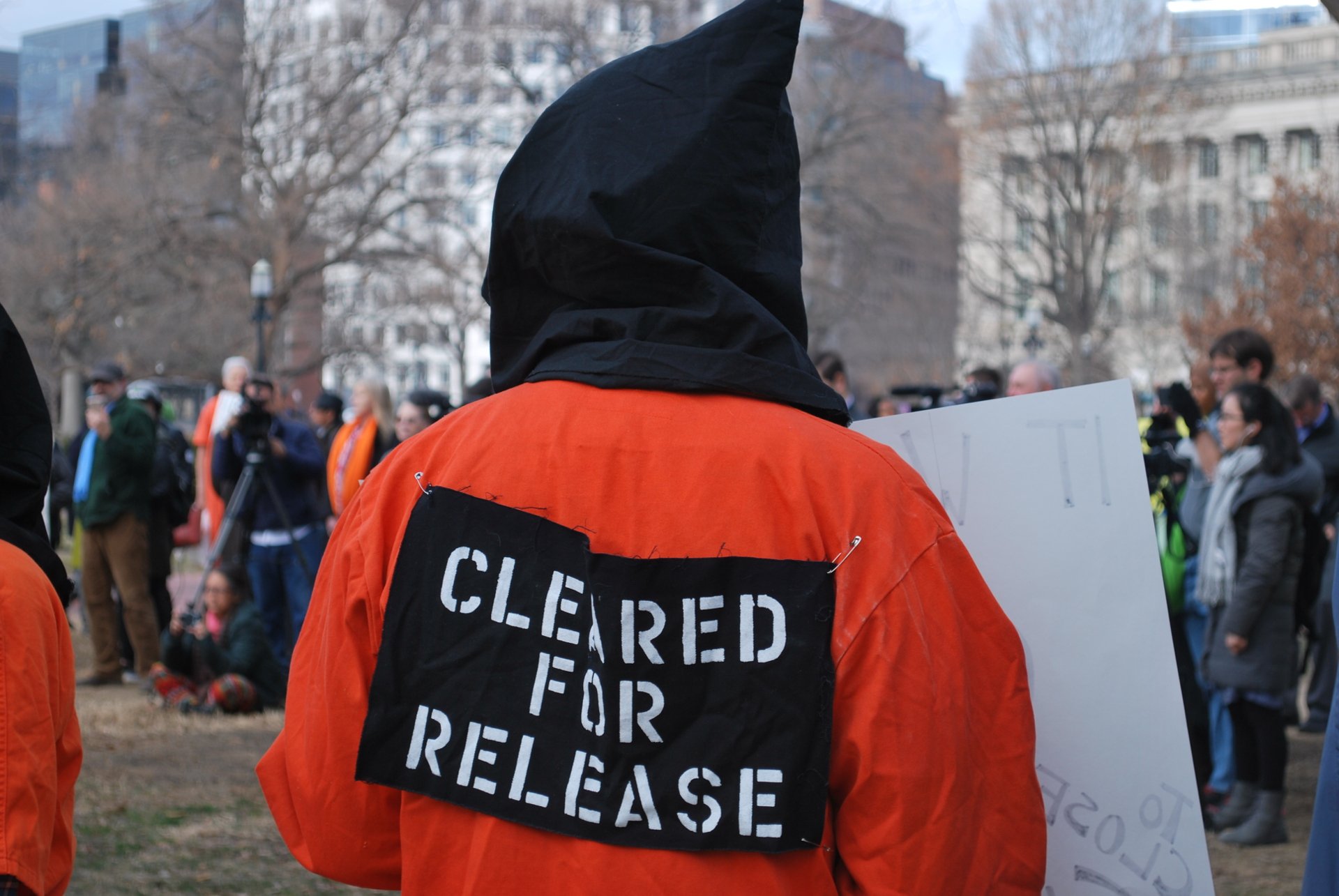

Obama’s Guantanamo Review Task Force issued its final report in January 2010. The task force included the Departments of State, Defense, Homeland Security, the Office of Director of National Intelligence, and Joint Chiefs of Staff. They reviewed 240 individual cases and approved 126 for transfer, referred 44 for prosecution in federal court or military commission, and determined that 48 others were “too dangerous” for transfer, “but not feasible for prosecution.” The remaining 74 were either still be investigated or were Yemenis who were cleared for release when conditions on the ground in Yemen improved.

Final report issued by Guantanamo Review Task Force in 2010.

In 2013, Obama enlisted a Periodic Review Board to determine whether people deemed necessary for continued detention could be released. That led to nearly two-thirds of men originally advised to remain in the prison to be transferred. But Obama fell short of closing the prison, a promise he made on Day 2 of his presidency.

Guantanamo remains a costly symbol of forever imprisonment and torture, and with Trump’s executive order, the prison will operate the way it has for the foreseeable future.

“By authorizing torture they thought that Guantanamo Bay would be able to hide that fact from the public,” Fallon told News Beat podcast outside the White House. “And so today, 16 years later from when the first detainees arrived there we still have people in custody down there who have not been brought to justice. We have some they’ve termed ‘indefinite detention,’ and it’s very discouraging as a country based on human rights and that promotes the rule of law that we will just ignore it right now. And so we will never bring those detainees to justice based on their torture, until we bring to justice their torturers.”

BLACK HOLE

On the front lines of the fight to get resolution for some of the longest-held detainees are attorneys like Shelby Sullivan-Bennis of Reprieve, which currently represents eight men in Guantanamo.

Two of Sullivan-Bennis’ clients were named in the January filing. Both have already been cleared for release.

One got the green light in 2010, but remains imprisoned. He’d even been measured for new clothing and given pain medication to help with the flight back home, but “that flight came and went,” she said.

Another of her clients was cleared by the six-agency panel who oversees individual detainee cases, and the U.S. and Morocco even struck a deal to bring the man home. Yet he also remains trapped at Guantanamo.

Sullivan-Bennis views the continued detention of detainees without charge as “illegal,” and has called upon the government to try the prisoners in federal court.

“The fact of the matter is that they have not given the opportunity to defend themselves in court to present evidence to say actually they weren’t in that location,” she told News Beat podcast across the street from the White House. “We have one client who was released who was accused of being a leader of a London al Qaeda cell. We were able to prove through documentation that he had never actually been to London.”

“It’s illegal and it’s been illegal ever since its inception,” said Sullivan-Bennis. “It was designed to be a prison outside of the law and there is no such thing and there should be no such thing.”

Pardiss Kebriaei, a staff attorney with the Center for Constitutional Rights, represents 43-year-old Sharqawi Al Hajj of Yemen, who has been detained at Guantanamo since 2004. But before that, he had been taken to various black sites on suspicion of being a “facilitator” for al Qaeda and was “brutally tortured,” Kebriaei told News Beat podcast.

“The surreal and torturous experience of his indefinite detention is layered on top of everything that came before,” she said in an interview amid the chanting of protestors. “And together it’s producing a deadening, numbing effect on him.”

Speaking of the lawsuit that she and others filed that morning, Kebriaei called the detentions “unprecedented..in the history of this country, there is no precedent for wartime detention of this length without charge that is still without end.”

“There is no precedent in the federal criminal justice system for holding people who have never had an adjudication of guilt, who’ve never been tried, charged and convicted who are simply being held on the basis of a preponderance of evidence,” she added.

Five of the 41 men still detained at Guantanamo have been cleared for release. Advocates worry that President Donald Trump won’t allow them to leave despite a six-agency government panel recommending they be transferred. (News Beat Podcast)

In an article she wrote for The Nation magazine, Kebriaei noted that a federal judge in 2011 “found that he had been subjected to ‘patent…physical and psychological coercion’—regular beatings, threats of electrocution, prolonged isolation, complete darkness, ear-splitting sound—and that statements from his interrogations that the government wanted to use to justify his detention were tainted and unreliable.”

Guantanamo and the cases of the people who remain there have become a distant storyline in the ongoing, global War on Terror, which has since become a borderless and seemingly endless war.

While Trump and others continue to advocate to transfer people from the battlefield to the island prison, perhaps for cheap political points, there’s growing evidence that the military commissions set up to prosecute alleged terrorists have become massive failures. Trump himself seemed to acknowledge this when he backtracked after claiming he’d consider sending the man who ran down people in New York City last year to Guantanamo, because prosecutions there move at a glacial pace.

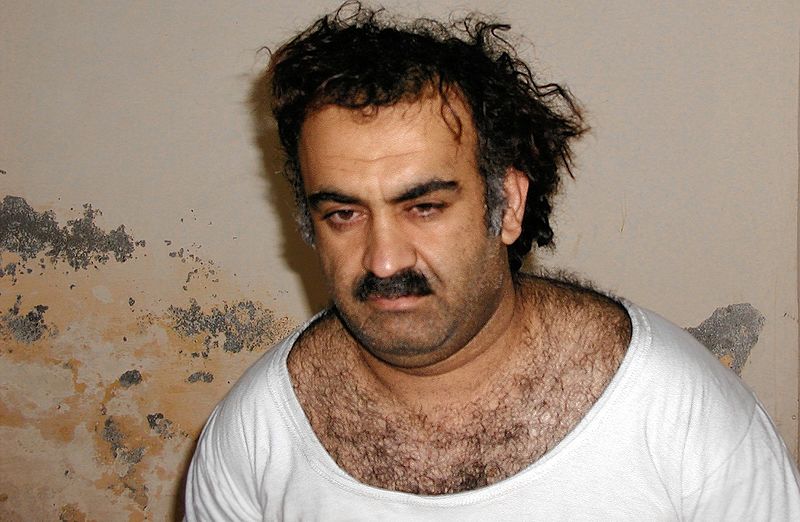

The most high-profile detainee at Gitmo, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, was arrested in 2003 but has yet to face a military commission. He has had more than two dozen pre-trial hearings, and reportedly won’t go before the commission until 2019, at the earliest.

“There’s every possibility that my client will die in prison before this process is completed,” David Nevin, Mohammed’s attorney, told the Guardian last year.

By contrast, federal courts in the United States have prosecuted a number of alleged al Qaeda and ISIS sympathizers over the years, though no one nearly as infamous as KSM, Mohammed’s nickname.

“There is law that binds the government and you can’t, just because we’re talking about detainees at Guantanamo, foreign Muslim terror suspects, apply a different set of rules,” said Kebriaei.

That’s just it. The United States did change the rules, and now it’s anyone’s guess when this era of forever detention will come to an end.