Just days before Christmas, Congress passed a bipartisan prison reform bill called The First Step Act, hailed as an answer to America’s over-bloated incarceration state.

The much-ballyhooed legislation came months after California became the first state in the country to abolish money bail in favor of a controversial computerized risk assessment system.

Meanwhile, a growing list of states and municipalities seeking to address prison reform on their own have done so by decriminalizing marijuana, reforming bail, or through investments in reentry services.

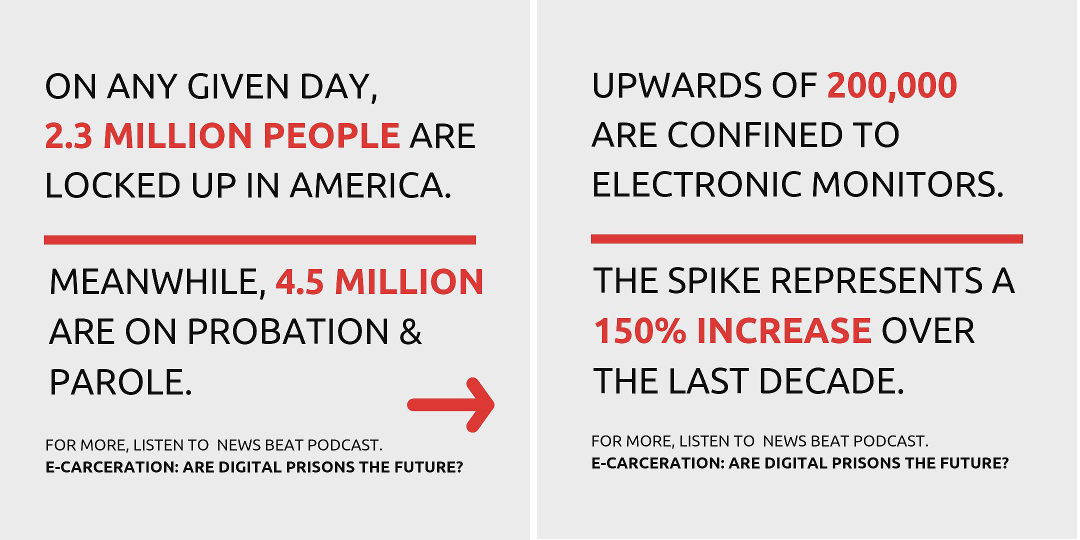

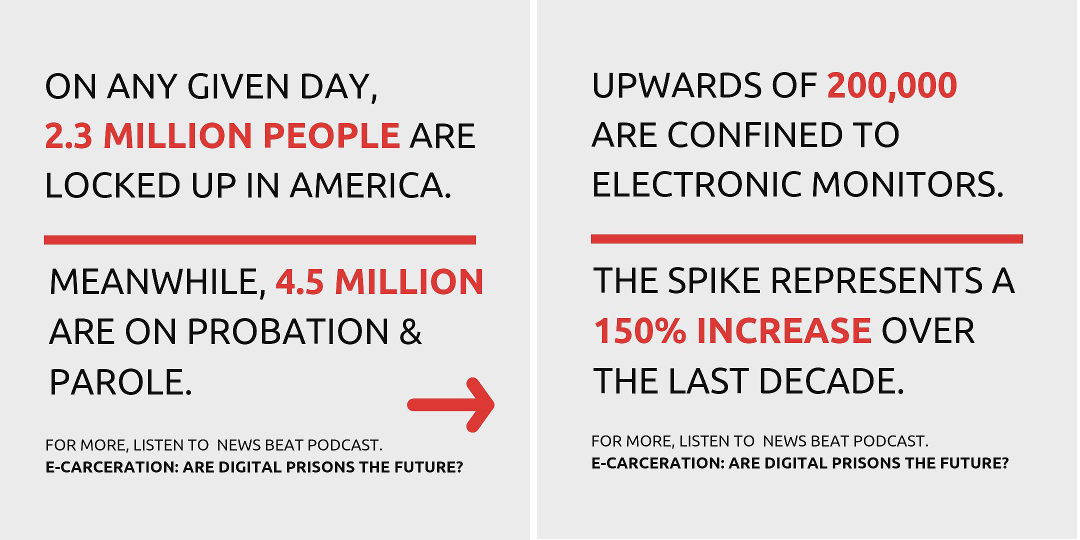

This newfound momentum toward decarceration comes as officials across the political spectrum are reconciling with the fact that the United States, after a decades-long push for stiffer criminal sentences, has become the world’s largest prison regime. On any given day, 2.3 million people are locked up inside jails and prisons, including hundreds of thousands who’ve never even been convicted of a crime, in pretrial.

At the same time, however, a parallel, but much less publicized fight has been brewing regarding the 4.5 million people confined to community supervision—more popularly referred to as parole and probation.

Just as the country’s incarcerated population ballooned since the 1970s, so too has the number of people in post-release and pretrial supervision, and consequently, more people than ever are under electronic monitoring (EM). This phenomenon has created a lucrative cottage industry in which companies are offering electronic monitoring devices to everyone from state correction services to federal authorities. Meanwhile, the continued blurring of the lines of state supervision and surveillance has raised privacy concerns, given the ubiquity of tracking tools already available to law enforcement in the form of license plate readers, Stingrays, and the virtual dragnet of security cameras, say prison reform and privacy advocates.

“We’re concerned because as we have this move toward decarceration, and trying to empty the jails and prisons that we’ve filled for the past several decades, that there’s this move toward electronic monitoring as a silver bullet to solve that problem,” Stephanie Lacambra, criminal defense staff attorney at Electronic Frontier Foundation, tells News Beat podcast. “Instead of having someone being monitored in custody, they are being monitored out of custody.”

DIGITAL PRISONS

It’s difficult to put an exact number on how many people are wearing these monitors, because of a lack of accounting. Reform advocates estimate there are more than 200,000 otherwise ‘free’ people required to be under electronic monitoring—a 150 percent increase throughout the last decade, according to the Center for Media Justice. Groups opposed to this form of 24/7 surveillance say it effectively extends someone’s incarceration, by imprisoning them inside their own homes, or within a specific geographic radius. Violations, even for the most minor of infractions, can land someone back in physical prison.

Join our email list and never miss an episode. Scroll to the bottom to sign up!

Law enforcement officials who support electronic monitoring—used in cases of DWIs, to track undocumented immigrants, youth justice, and increasingly for pretrial release—frame this technology as an alternative to incarceration, enabling those in its invisible shackles to ostensibly live ‘free’ lives.

It’s this line of thinking that raises alarm bells among reformers. They contend that the increasing use of electronic monitoring, ironically as officials are simultaneously making a conscientious effort to decarcerate, is just another way to imprison millions of people, albeit by sequestering them in Orwellian digital prisons instead of behind the steel bars and barbed wire-draped walls of stereotypical lockups.

Count Myaisha Hayes, national organizer on criminal justice and technology at the Center for Media Justice, as among the reform advocates anxious about what the future of incarceration will look like.

“Is the sort of decarceration that we’re demanding a fundamental shift in how we respond to harm and maintain public safety?” she asks. “Or is a demand to decarcerate about evolving our criminal justice system with technologies that creates digital prisons that we’re going to have to contend with years later down the line, when we see a crisis happening with so many people being incarcerated in their homes by these devices?”

Author and social justice activist James Kilgore is all-too-familiar with the “dehumanizing” feeling of walking around with an ankle monitor and is using that experience to speak out about potential abuses by the system.

Kilgore is the project director for the initiative Challenging E-Carceration, and collaborated with Hayes and others at Center for Media Justice to produce a report called #NoMoreShacklesReport released last year. It highlights the explosive growth of state supervision, and the role electronic monitoring plays in tracking people. [Read the full report here.]

“Of all the conditions imposed on individuals on parole, likely none is more intrusive, punitive and dehumanizing than electronic monitoring,” it states.

The probation population quadrupled between 1980 and 2015, from 1.1 million to 4.3 million, according to the report. There was a similar rise in the number of parolees, from 220,400 to more than 826,000.

“Not only did the number of individuals on parole rise, but the conditions of supervision became much more stringent,” continues the analysis. “Though regulations and practice vary from state to state, typical parole conditions now include regular drug testing, a ban on associating with individuals with a criminal record, and an extensive set of fees and fines.”

Kilgore wore a monitor for a year in 2009 as a condition of his parole.

The electronic monitor, which is affixed to someone’s ankle, contains GPS technology, and alerts authorities if it’s tampered with, made even the most mundane human interactions uncomfortable.

“I felt like I was still under carceral control, which I was,” he says. “And the image that always comes to me, is the fact that when I went to sleep at night, I felt as if my parole officer was laying across the bed looking up at me from under the covers.”

Kilgore bristles at the suggestion that walking around with an ankle monitor—or “shackles”—is a more compassionate form of punishment.

“Most people just said, ‘Well, it’s better than jail,’” he tells News Beat. “And my response was always, Well that’s true, but a minimum-security prison is better than a supermax, but it’s still a prison. And by the same token, at an individual level, I would never tell someone, Well, you’re better off staying in prison or in jail than going out on an electronic monitor.

“Just like I wouldn’t tell somebody, Well, stay in that supermax where you’re in solitary 24 hours a day, and don’t go to this camp where you can be out free, you know, [for] 16 hours a day, moving around the yard and so forth.”

This all comes amid a period in which lawmakers of all stripes are coalescing around finding alternatives to incarceration, says Hayes.

“You see these devices used as a condition of pretrial release, parole and probation, much more frequently now,” she adds. “These devices are even used on youth. And we also know that around 30 to 50,000 immigrants are also placed on these devices. So the reason why electronic monitoring is being considered as an alternative…is really in response to the demand to decarcerate.”

Private Prisons & Privacy

Also adding to the growing list of concerns is the fact that the four largest providers of electronic monitors are private prison companies, including the most profitable, GEO Group, which has secured lucrative government contracts to operate federal prisons and monitor people in immigration proceedings.

According to the Center for Media Justice’s report, BI Incorporated, a subsidiary of GEO Group, has government contracts with at least 11 state departments of correction, and earned nearly $84 million in revenue in 2017.

In a recent press release, BI billed itself as “the leader for offender monitoring products and services in community corrections,” and works with 1,400 correctional agencies throughout the United States, Canada and Europe.

BI, which is based in Boulder, Co., reportedly has earned more than a half billion dollars in U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) contracts since 2004. The funding is mostly related to the company’s involvement in ICE’s Intensive Supervision of Appearance Program, which includes monitoring via ankle devices. The program itself is advertised as an alternative to incarceration—what reformers fear could become the norm in typical criminal proceedings.

Last year, bestselling author and civil rights lawyer Michelle Alexander echoed that sentiment in a New York Times piece titled “The Newest Jim Crow”—a play off her critically acclaimed book “The New Jim Crow.”

“Even if old-fashioned prisons fade away, the profit margins of these companies will widen, so long as growing numbers of people find themselves subject to perpetual criminalization, surveillance, monitoring and control,” she writes.

As private prison operators profit off these devices, those forced to wear them are often charged for its daily usage, ranging from $3 to $35 per day, and one-time installation. The cumulative cost can be expensive, and shift to the digitally incarcerated, advocates say.

The devices themselves are GPS-enabled, and can either share real-time data, or provide a next day downloadable report for corrections officials, according to the privacy and civil liberties nonprofit, Electronic Frontier Foundation.

Those sounding the alarm on privacy grounds say electronic monitors can be intrusive, and even ensnare other individuals within close proximity around them.

“Locational privacy has been a concern in the deployment of a number number of different law enforcement surveillance technologies, from automated license plate readers to the use of facial recognition,” says Lacambra, the criminal defense staff attorney at EFF and former indigent criminal defense trial attorney.

“I think we should be concerned about location tracking,” she adds. “Not just in the context of electronic monitoring, but in all of these other contexts as well, because I think they give law enforcement the potential to really aggregate very detailed profiles about all of us, regardless of whether you’re on probation or parole or awaiting trial.”

In her past work, Lacambra observed electronic monitors being deployed more and more in cases of pretrial release. Historically, when someone was released on their own recognizance ahead of a trail, they’d be free without restrictions. With these devices making it much easier for officials to track someone’s movements, courts now have another option at their disposal.

“Even if you’re lucky enough to be set ‘free’ from a brick-and-mortar jail thanks to a computer algorithm, an expensive monitoring device likely will be shackled to your ankle—a GPS tracking device provided by a private company that may charge you around $300 per month, an involuntary leasing fee,” writes Alexander in her Times column. “Your permitted zones of movement may make it difficult or impossible to get or keep a job, attend school, care for your kids or visit family members. You’re effectively sentenced to an open-air digital prison, one that may not extend beyond your house, your block or your neighborhood. One false step (or one malfunction of the GPS tracking device) will bring cops to your front door, your workplace, or wherever they find you and snatch you right back to jail.”

In raising awareness about the prevalence of ankle monitors, Hayes sees a unique opportunity to step back, and in her view, stem the growth of these all-seeing GPS devices, before they become universally accepted.

“As we’re in this moment of bail reform, parole justice, all of these different issues within the criminal justice space, we have a real opportunity to take a pause and think about, Okay, if we’re going to end monetary bail, you know, how do we actually address harm and maintain public safety in our communities?” she says. “Or do we want to just find a technological solution to this issue? I think that’s the issue that we’re having to deal with, and I do think…we have an opportunity now to course-correct.”