The pilot was getting impatient.

Moments earlier, his gunship and another had indiscriminately shredded a group of men in New Baghdad, Iraq with a barrage of machine gun fire, when a dark minivan hurriedly pulled up to the scene.

Two unarmed men emerged, peeled around the sidewalk, and crouched down. They hoisted one of the wounded off the ground and scampered to the van’s open door.

The U.S. airmen watched the rescue attempt from above, growing increasingly agitated as they awaited further commands.

“We have a black SUV—uh, Bongo truck picking up bodies,” one pilot reported.

“Fuck!” lamented another.

“Request permission to engage.”

The next 15 seconds or so are difficult to stomach. There’s another torrent of bullets and men desperately fleeing for cover. The van fails to escape the high-powered artillery deluge. Inside the vehicle, two young children are seriously wounded—witnesses to an unspeakable tragedy very nearly hidden from history.

On April 5, 2010, the anti-secrecy organization WikiLeaks published cockpit footage from the U.S. Apache gunships involved in the incident. It documented the slaughter of more than a dozen people, including two Reuters journalists. Dubbed “Collateral Murder," the 39-minute video sent shockwaves around the world, as millions watched the U.S. military murder innocent civilians.

The long-sought footage was leaked by a U.S. Army Private First-Class, named Chelsea Manning, then known as Bradley. Manning also provided WikiLeaks with thousands of military documents and diplomatic cables that separately became known as the “Iraq War Logs” and “Afghan War Diary.” Among the more haunting revelations: evidence that U.S. troops executed at least 10 Iraqi civilians and ordered an airstrike to cover it up.

[RELATED: Listen to "Collateral Murder Cover-Up" to Learn More About Whistleblower Chelsea Manning]

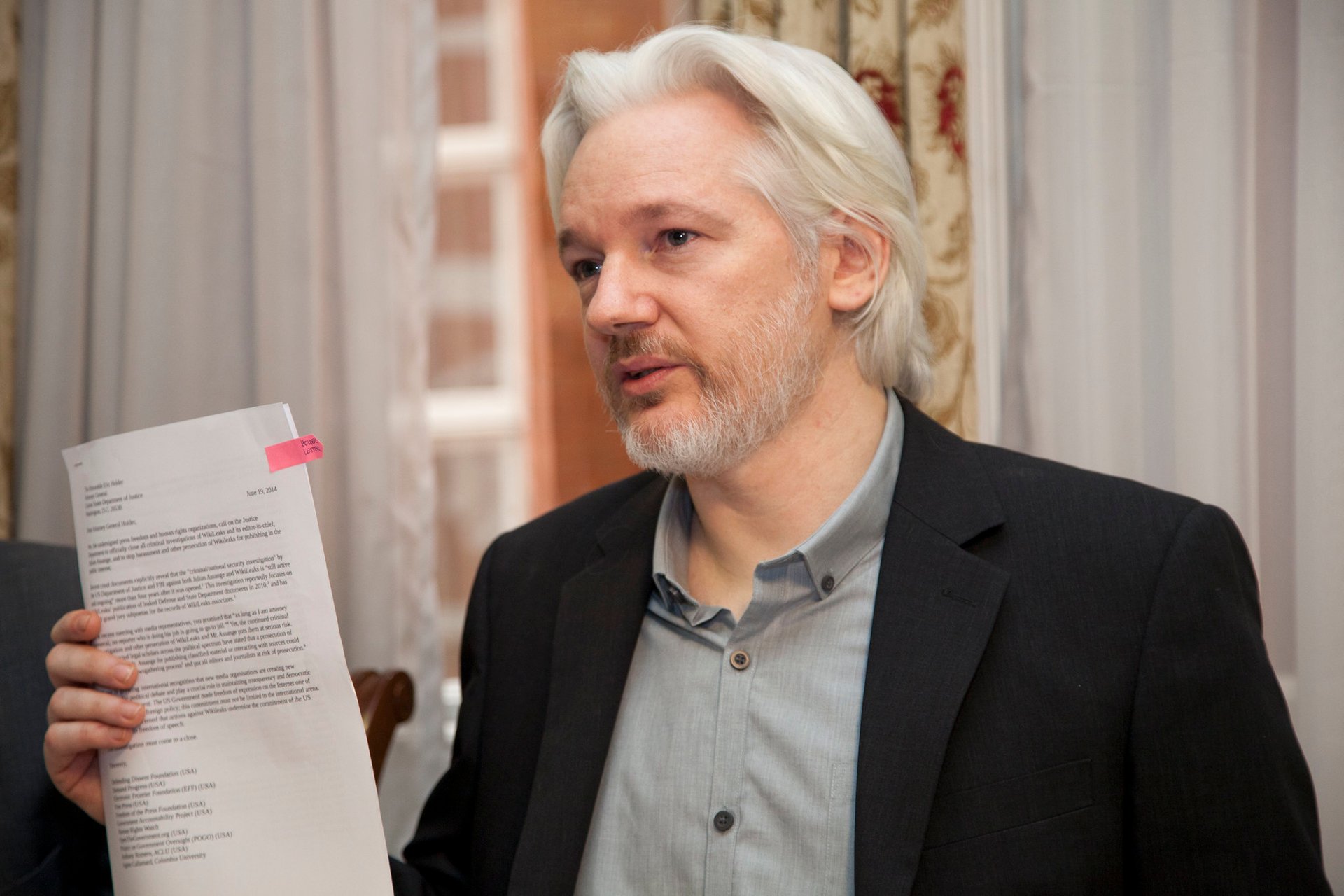

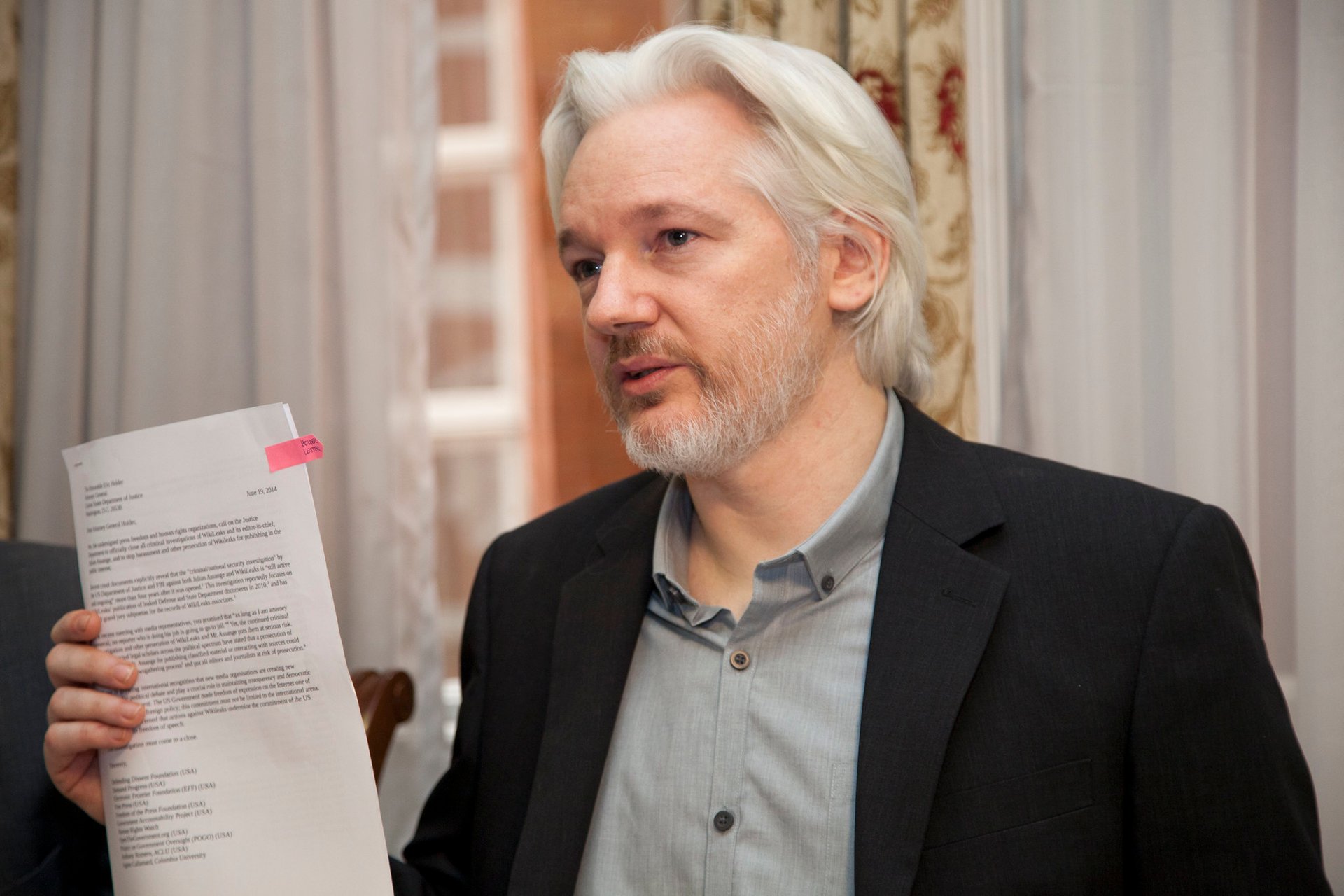

WikiLeaks Publisher and Co-Founder Julian Assange instantly garnered worldwide notoriety—fervently praised in some circles and utterly despised in others. Later, he was accused of sexual assault in Sweden, which he denied, and petitioned the Ecuadorian government to grant him asylum at its embassy in London, where he lived in a state of self-imposed imprisonment for seven years until that protection was revoked in 2019.

(WikiLeaks Co-Founder and Publisher Julian Assange in 2019 was indicted under the Espionage Act, allegations stemming from disclosures provided by whistleblower Chelsea Manning. Photo credit: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ecuador)

Shortly after, the Trump administration escalated the U.S. government’s long campaign to discredit WikiLeaks. Within a span of six weeks, beginning April 11, the U.S. Department of Justice charged Assange with cyber crimes and 17 counts under the Espionage Act. He’s currently being jailed as he awaits an extradition hearing in the United Kingdom.

Assange is but one of an ever-growing list of people indicted under an archaic law that’s recently been weaponized against journalistic sources.

The number of Espionage Act cases has exploded over the last two decades, with the ostensibly liberal Obama administration prosecuting more people under the law than all presidential administrations combined. The targets have not been spies—as was intended when the Espionage Act was passed during World War I—but whistleblowers disseminating valuable information to the American people through journalists.

The law is so oppressive, lawyers argue those charged can’t mount an effective “public interest” defense—among the reasons why National Security Agency (NSA) leaker Edward Snowden has sought refuge elsewhere.

The Assange indictment, however, is a game-changer. For the first time in U.S. history, a publisher has been charged under the Espionage Act for revealing classified information.

“Whether or not you like Assange, the charge against him is a serious press freedom threat and should be vigorously protested by all those who care about the First Amendment,” Trevor Timm, executive director of the nonprofit Freedom of the Press Foundation, said in a statement last year.

HISTORY OF THE ESPIONAGE ACT

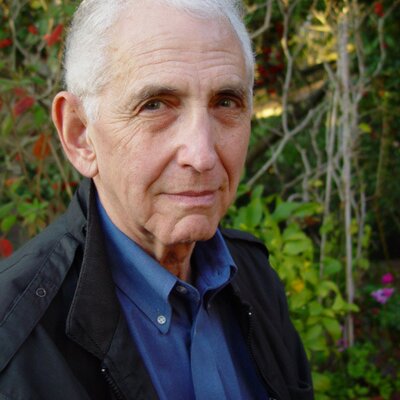

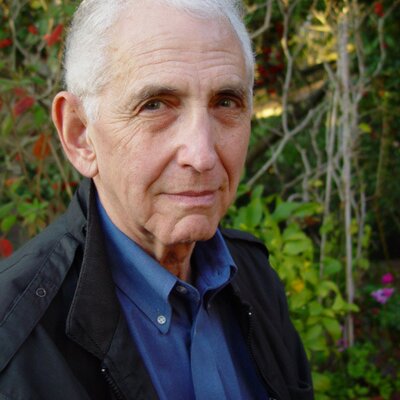

Perhaps the most infamous Espionage Act case in modern history was the one the Nixon administration brought against Daniel Ellsberg, the famed Pentagon Papers whistleblower who leaked classified documents revealing, among other seismic truths, that the U.S. government was flat-out lying about key aspects of the bloody, disastrous Vietnam War.

On June 13, 1971, The New York Times published its first story based on Ellsberg's disclosures, a secret history of the war commissioned by then-Defense Secretary Robert McNamara three years earlier.

“A massive study of how the United States went to war in Indochina, conducted by the Pentagon three years ago, demonstrates that four administrations progressively developed a sense of commitment to a non-Communist Vietnam, a readiness to fight the North to protect the South, and an ultimate frustration with this effort—to a much greater extent than their public statements acknowledged at the time,” wrote Times reporter Neil Sheehan.

The following day, President Richard Nixon’s attorney general, John Mitchell, sent the Times a telegram warning that publication of the material was prohibited under Section 793(e) of the Espionage Act, and urged the paper to return the documents to the Department of Defense.

(Pentagon Papers whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg. Photo credit: Twitter)

"Moreover, further publication of information of this character will cause irreparable injury to the defense interests of the United States,” Mitchell warned.

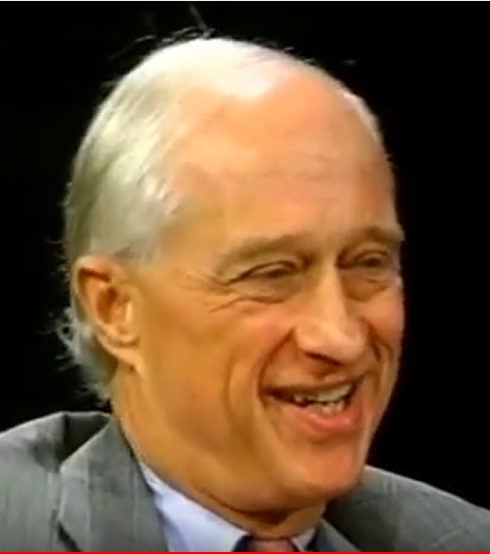

James Goodale, a First Amendment attorney who served as vice president and general counsel of The New York Times at the time, was adamant that the paper should publish, though consulting attorneys disagreed. Goodale won the argument, and helped develop the newspaper’s appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

After an injunction was issued, Ellsberg, who worked for the global research and analytics nonprofit RAND Corporation, provided the documents to The Washington Post, and on June 18, 1971, that paper began publishing its own series based on the Pentagon Papers. The Post joined the Times in its appeal to the Supreme Court, and on June 30, the court ruled 6-3 in the papers’ favor, a landmark decision that overruled the government’s claim of enforcing “prior restraint” to prevent publication of secret material.

Goodale was confident the Times had a winning legal argument.

“Anyone, I would have thought who knew anything about the First Amendment, would know that you can't censor publications in [the] United States,” he says. “And when the government comes in and asks a court to stop publication, that is a form of censorship. So I always thought from the beginning we would win. And I was right. And I may have been more confident than other people involved with the case.”

“It was unconstitutional,” adds Goodale, who for five years served as chairman of the board for the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), a global press freedoms advocacy group.

Before the Pentagon Papers case, there was little applicable law related to the Espionage Act and press freedoms, Goodale notes.

That was because after the law was passed in 1917 it was mostly used to go after socialists and antiwar critics, says Peter Sterne, managing editor of the U.S. Press Freedom Tracker, which analyzes and catalogs anti-media abuses.

“Originally, at least, the Espionage Act did not include any...anti-press provisions,” Sterne tells News Beat podcast. “It was solely target at the criminalization of espionage and particularly the criminalization of disseminating and sharing sensitive national security information. But it did not allow the president to order newspapers not to print certain information. Much later, decades later, the Espionage Act would be marshaled in a way that was anti-press.”

In 1918, Congress passed amendments to the law that collectively became known as the Sedition Act. It made it illegal to “willfully utter, print, write or publish any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government of the United States or the Constitution of the United States” and to “publish any language intended to incite, provoke, or encourage resistance to the United States, or to promote the cause of its enemies.”

“The Sedition Act went after basically domestic critics of the war, who by opposing the war and especially by opposing the draft, was seen as helping the enemy,” says Sterne. “And that was immediately used to go after a lot of domestic critics of the war, especially socialist activists.”

Among the most infamous early Espionage Act cases involved Eugene Debs, founder of the Socialist Party of America, who ran for president four times—garnering 6 percent of the vote in the 1912 election.

In June 1918, Debs gave a speech outside a prison in Canton, Ohio holding three people convicted under the Espionage Act. While Debs was careful with his word choice—noting, for instance, “I must be exceedingly careful, prudent, as to what I say, and even more careful and prudent as to how I say it—he was nevertheless charged with 10 counts under the Espionage and Sedition acts and sentenced to 10 years in prison. A year later, the Supreme Court upheld his conviction in a unanimous decision, dismissing a First Amendment argument by Debs.

“Going after domestic critics of the war did not violate the First Amendment, because by opposing the draft and encouraging people not to cooperate with it, they were harming American national security,” says Sterne, summing up the Supreme Court’s ruling.

The number of espionage cases was few and far between in the years that followed World War I. One near-constitutional collision came when a federal grand jury was impaneled to investigate the Chicago Tribune for an article that appeared to indicate that the United States had successfully cracked Japanese codes before the Battle of Midway. The newspaper was spared when the grand jury declined to return an indictment.

The aforementioned Pentagon Papers case changed everything. Not only did the government attempt to argue “prior restraint” involving classified material, but the targeting of an alleged leaker indicated that the Justice Department could potentially broaden the pool of people it could prosecute under the Espionage Act.

Yet another turning point in the history of the law were three cases during the Reagan administration: the attempted prosecution of the author James Bamford; former CIA Director William Casey threatening several news outlets with espionage prosecutions; and the conviction of Samuel Morison, a U.S. Navy intelligence analyst, who released spy satellite photos to a British magazine.

For a while, Morison was the only leaker successfully prosecuted under the Espionage Act. Not anymore.

War On Whistleblowers Takes Hold

Upon assuming the presidency in 2009, Barack Obama promised to launch a “new era of open government.”

“In the face of doubt,” Obama said in a January 2009 memo, “openness prevails.”

Obama’s pledge had deep resonance, considering the opaqueness of the previous administration, one that was rocked by myriad scandals, from its controversial entrance into Iraq and mass abuses at Abu Ghraib prison to its torture and rendition regime and illegal NSA wiretaps.

Despite his grandiose promises regarding transparency, however, Obama largely failed to live up to the mission he laid out on his first days in office. In fact, the Obama administration was the most aggressive in history in pursuing leak investigations, so much so that more whistleblowers were prosecuted under the Espionage Act during his tenure than all other presidents combined.

Obama’s Justice Department prosecuted eight people under the Espionage Act, including Manning, Snowden, NSA whistleblower Thomas Drake, and CIA analyst John Kiriakou, who sounded the alarm about the agency's torture program. Journalists and newsrooms were also caught in the dragnet. Former New York Times investigative reporter James Risen fought off attempts by the DOJ to reveal the identity of his source behind a chapter in his book about a botched operation to sabotage Iran’s nuclear operation. The Associated Press had phone records seized as part of a probe into a failed al Qaeda terror plot. And although he wasn’t prosecuted, federal prosecutors named a Fox News reporter as a co-conspirator in another leak case.

In 2013, the Committee to Protect Journalists issued a scathing report on the Obama administration’s press record at the time.

“Journalists and transparency advocates say the White House curbs routine disclosure of information and deploys its own media to evade scrutiny by the press,” it states. “Aggressive prosecution of leakers of classified information and broad electronic surveillance programs deter government sources from speaking to journalists.”

In effect, press advocacy groups were warning about a possible chilling effect that would preclude future whistleblowers from speaking out.

“They cautioned that prosecution of individuals who leaked information to the press, as the Obama administration had started to do, would basically create an even greater culture of secrecy than the government had already instituted up until that point,” Carrie DeCell, a staff attorney at the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University, tells News Beat podcast. “And create widespread chilling effects, both for individuals within government who would want to share important information with the press and with members of the press themselves, who could also fear prosecution under the Espionage Act.”

The Trump administration has basically picked up where Obama’s DOJ left off, having indicted at least four people under the Espionage Act. They include Reality Winner, Terry Albury, Daniel Hale, and Assange. (Both Winner and Albury pleaded guilty to their respective charges. Hale’s attorneys in September 2019 moved to have the indictment dismissed, in part arguing: the act’s “imprecise language and ambiguous reach is a chilling effect on constitutionally protected speech and press activity.”)

“I think it's totally outrageous,” says Goodale, the former general counsel of The New York Times. “I think it violates the First Amendment. I think Obama really disgraced himself with respect to bringing leak prosecutions...Okay, let's pretend it is 1971. Have there ever been any leak prosecutions? No. Have there been any prosecutions for publication after the fact like Assange? No. Nothing.

“And everybody thought that's what it should be,” he continues. “And you'll see that governments have gradually brought criminal cases for leaking, for failing to disclose sources, and that Obama was the one who did the most of it. And it's outrageous.”

While mainstream media organizations have for the most part resisted defending whistleblowers on their editorial pages or in public, the Assange indictment had a different effect. In indicting Assange, the Trump DOJ was effectively saying any publisher can be held accountable for disclosing classified information—a step even too far for the hawkish Obama administration.

“No matter what you think of Julian Assange as an individual, the way that the government has chosen to prosecute him under the Espionage Act raises serious concerns for all members of the press, particularly those who rely on the disclosure of classified information,” says DeCell.

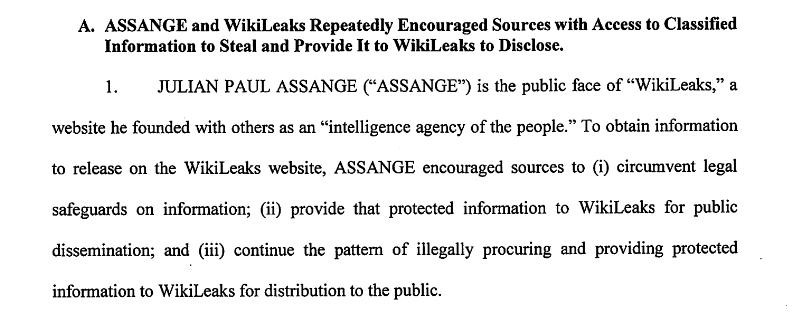

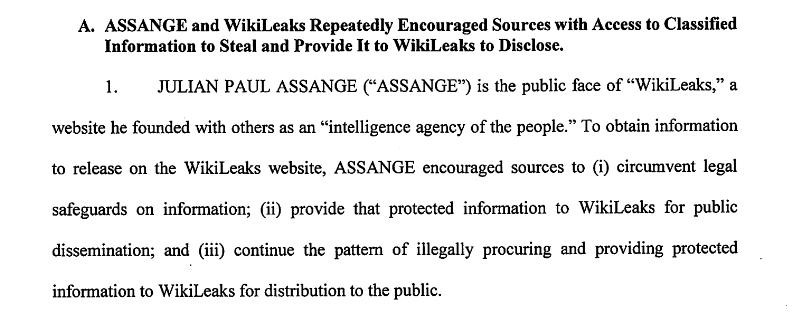

Assange was initially indicted on a conspiracy computer charge for allegedly helping Manning in her attempt to break a password. Investigators also accused the WikiLeaks publisher of encouraging Manning to provide more information.

Press freedoms advocates have dismissed Assange’s alleged illegal journalistic activities as general tricks of the trade.

“The indictment singles out efforts to cultivate sources and to solicit information from sources,” says DeCell. “And the Justice Department actually, in describing the indictment, highlighted those features as something that might distinguish Julian Assange from other journalists.”

“But those features don't distinguish Julian Assange from other journalists at all,” she continues. “Just because Julian Assange reached out to Chelsea Manning on a number of occasions through secure communications to encourage her to disclose more information about the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, you know, again, doesn't distinguish Assange from any other national security reporter who would reach out to sources for the same exact kinds of information.”

So where does Goodale, the prominent First Amendment attorney, stand on the issue of Assange’s case?

“I think they're terrible. Terrible!” Goodale tells News Beat podcast. “What the government is trying to do is they're trying to create an ‘Official Secrets Act,’” that would criminalize both leaking and publishing classified information.

Among the most frustrating aspects of leak investigations for whistleblower advocates is context often lost in the discourse about the leaker’s motivations. Current and former government officials often hit the airwaves to discredit sources. And the media falls into regrettable traps, airing segments debating whether the leaker should be characterized as a “traitor” or “hero.” Rarely is the content of the disclosures analyzed and put into context.

From DeCell’s point of view, the post-9/11 era has been especially enlightening.

“There are a number of things that we have learned through leaks to the press, leaks of classified information that the government wants to hold secret,” she says. “We've learned about prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib and at Guantanamo [Bay]. We've learned about drone strikes against not only enemy combatants, but also civilians. We've learned about the widespread surveillance of Americans under an NSA program, thanks to Edward Snowden. And we've been engaged in robust public debate about whether or not these policies are appropriate for the government to continue pursuing.”

“And without that information, we can't really call ourselves a democracy with an accountable government. So I think the Espionage Act is being used to protect government secrets, to the detriment of our ultimate democratic ambitions.”