Afterward, the couple returned to his fiance’s parents’ two-family home in Queens and called it a night.

While they were asleep, a woman was being brutally raped and sodomized inside a Bronx park at 4 a.m. The hideous crime escalated when the attacker brought the victim into an abandoned building after she attempted to escape in a cab and raped her a second time, leaving her with a gruesome cut over her eye. The $15 she had on her at the time was also gone.

Five days later, the police came knocking on Newton’s door. It was one of those hot and steamy summer days. His family was over. The cops gave Newton two options: Leave willingly or in handcuffs. He went peacefully.

Newton racked his brain while inside the precinct.

“Why am I here?”

“Why am I in this jail cell?”

It didn’t take long for Newton to get his answers, and the “truth” hit him like a ton of bricks. The victim of the Bronx attack had identified Newton as her assailant while scrutinizing a book of photos the police maintained. (Newton had been arrested years prior for a fight over a money dispute.) He was also pegged as the perp during a lineup of potential suspects, and later charged with a slew of crimes, including rape.

Less than a year later, Newton was convicted of raping the woman and was sentenced to upwards of 40 years behind bars. He was put on a bus bound for a western New York prison.

“We actually had the ticket stubs to the Ghostbusters when it came out in 1984,” Newton says. “We had the evidence; where we was, in a different borough, in Queens County. But they was hell bent on making an arrest regardless of the circumstances.”

“There was no way I could’ve left Queens County to commit this crime in Bronx County, drive over a bridge, and be able to drive back home, and you know, be able to, you know, get back into a two-family house,” Newton adds.

Newton confessed to nothing and maintained his innocence for 21 long, arduous years. He repeatedly appealed the conviction on his own behalf. His entreaties never amounted to anything. He first petitioned the courts for post-conviction DNA testing in 1994; it was denied. Exactly a year later, with the help of nonprofit the Innocence Project and the Bronx County District Attorney’s Office, Newton caught a break. The rape kit, which officials said could not be located and was thought to be destroyed, was discovered in a warehouse in Queens. Seven months later, after the DNA in the rape kit was tested, Newton was exonerated.

‘SECOND SENTENCE’

Sadly, Newton’s story is one that’s become all-too familiar throughout the past three decades. Since 1984, more than 2,000 people have been exonerated of crimes they didn’t commit—spending a collective 18,000 years in prison, according to the National Registry of Exonerations. In one sense, there’s good news: Year after year, more and more people are getting exonerated. 2016 saw the highest number of exonerations (168), ever. But in another sense, an exoneration is an admission by the state, sometimes grudgingly, that it failed miserably in exacting justice. Oftentimes, those who have been proven innocent emerge from prison with absolutely nothing to help facilitate life afterward.

No identification. No prescription eyeglasses. Nowhere to sleep. No job prospects.

This horror is made excruciatingly more painful by the fact that many of these people even struggle to receive compensation for the years they spent locked up from the very same institutions that erred in charging and convicting them for crimes they did not commit. Only 32 states in the United States have exoneration compensation statutes on the books for people who were wrongfully convicted. In some instances, the laws fail to offer proportionate compensation to exonerees in relation to how many years they lost behind bars. And of the states that have such laws, most are “woefully inadequate,” Rebecca Brown, director of policy at the Innocence Project, tells the U.S. News Beat podcast team.

In New York, for example, the wrongfully convicted—in some cases, people who were locked away before the first iPhone was released, and with little or no basic understanding of law or statutes ostensibly created to assist them following exoneration—are expected to sue the government for damages. Other states cap the amount a person can receive over their lifetime, while others insert legal caveats that make it almost impossible to receive compensation. A wrongfully convicted person in New Jersey who pleaded guilty to the crime in which they were convicted, for instance, is not entitled to any monetary award.

“It’s basically a second sentence,” says Brown. “And so the least that we can do—the least we can do—is provide restitution, provide compensation so that people are in a position not just to survive, but to thrive.”

Some exonerees take the fight for compensation to their grave.

Perhaps one of the most tragic examples involves a Louisiana man named Glenn Ford, who in the ’80s was wrongfully convicted of killing a man. He wasted away in prison, developing lung cancer, and fighting for his innocence until he was finally exonerated. Compensation laws in Louisiana make it incredibly difficult for an exoneree to receive even a penny. Ford died without being awarded any money from the state.

Emily Bazelon, a staff writer for New York Times Magazine and co-host of the Slate Political Gabfest podcast who has reported on Ford’s fight for compensation, said Louisiana’s statute caps the amount an exoneree can receive at $250,000. In Ford’s case, even if he had been compensated it would have meant a little more than $8,000 for each year he spent locked away—almost half of what a minimum wage worker in the state earns annually. (Exonerees can also earn an additional $80,000 for opportunities lost while incarcerated.)

Before he died in June 2015, Ford was found ineligible to receive any type of restitution because of a “factual innocence” provision included in Louisiana’s law, says Bazelon.

“Louisiana interprets that to mean that you have to show you didn’t commit not only the crime that you were convicted for, but any crime based on the same set of facts,” she explains. “And so, in Ford’s case, the state Attorney General’s Office…argued that Ford did not have ‘clean hands,’ meaning he wasn’t totally innocent. Because after [the victim] was killed, Ford told the police that he knew about the plans for the robbery and pawned some of the stolen jewelry and tried to sell the gun that was used in the murder.

“Ford’s lawyer argued that he cooperated with the police because he implicated the real killer,” Bazelon continues. “But they came up basically with these minor crimes that he had never been charged with and hadn’t been able to prove his innocence on, and they used those crimes to deprive him of his eligibility for any kind of monetary compensation from the state.”

FIGHTING FOR EXONERATION COMPENSATION

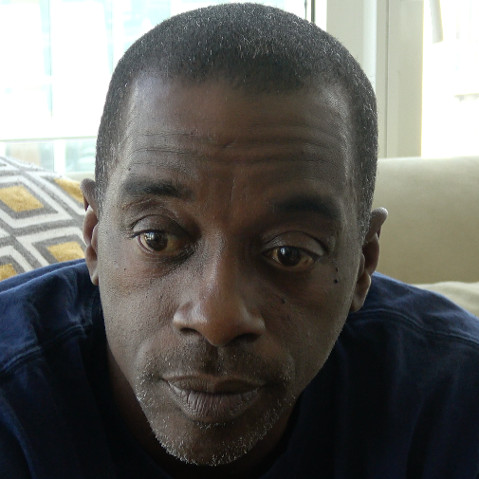

Despite being locked away for a crime he didn’t commit—no less a brutal rape, which carries its own stigma in and out of prison—Newton considers himself one of the lucky ones. So far, he’s received $12 million in compensation from New York City, but has yet to receive a dime from the state.

“In regards to states that don’t have compensation, that just flatly refuse to do anything in regards to helping people, it’s left on people that have good will,” Newton says from his Brooklyn apartment.

“You talk about the hurricane that we’re experiencing now and how people of good will [are] reaching out, it’s other exonerees like myself that have reached out to other exonerees and have helped them out with basic things,” he continues. “And I can say that, and I can do that, because I’m also an exoneree that received assistance from other exonerees while I was waiting to get compensated in my 11 years (outside of prison).”

Newton doesn’t take this new responsibility lightly. He knows more people will continue to be exonerated. The last three years alone saw more exonerations than from 1989 to 1999 combined. And records continue to fall: More people in 2015 were exonerated for homicides (58) than ever before, including five who had been sentenced to death, according to The National Registry of Exonerations. Underscoring Newton’s insistence that exoneration compensation statutes become the norm throughout the land is the fact that in 2015 alone, 18 exonerees were wrongly convicted of various crimes in states with no such law.

“So we go back into these other states with the policy staff of the Innocence Project and speak to these politicians and try to get access to the legislature and just advocate: Why don’t y’all want compensation?” Newton asks. “Why do y’all refuse? And their attitude, a lot of times, [is] that these men and women should just be glad that they’re home, they should just be glad that the system finally worked for them. No the system didn’t work…if it really did work it would finish working by compensating and passing these laws to help them out.”

It’s a fight that started on that steamy June day in 1984 when the NYPD knocked on the wrong man’s door, and it’s a miscarriage of justice that Alan Newton will continue to try to shed a light on, in the hopes that perhaps one day, even though the wrongly convicted won’t ever fully be compensated for their lost time, and dreams, they can possibly have a chance at survival.