In the month since George Floyd was killed by a Minneapolis police officer, intense protests have erupted across the country, forcing America to reckon with centuries of oppression and brutalization of Black people.

Floyd’s slaying has sparked renewed discussions surrounding a host of racial issues. Not only are people acknowledging their own biases, but opening their eyes to systemic racism, foundational inequities within society, and police brutality.

Discussions of police misconduct have folded into a more sweeping conversation about the legitimacy of police and whether the contemporary model—characterized by massive budgets, militarization, and a warrior culture—is antithetical to an ostensibly free, democratized society. Concepts usually dismissed as “too radical,” most prominently, defunding the police and police abolition, have moved out of revolutionary circles and into the public space—with slogans quite literally painted on city streets.

In death, Floyd has become a symbol of not only endemic police violence but more glaring societal ills that have historically plagued Black Americans, including economic, health, environmental, and educational disparities.

While activists of all generations, genders, and races have eagerly embraced this movement and united in outrage over the death of George Floyd, among so many other unarmed Black men who've been killed by law enforcement, Black women are similarly exposed to excessive police violence yet routinely forgotten or ignored.

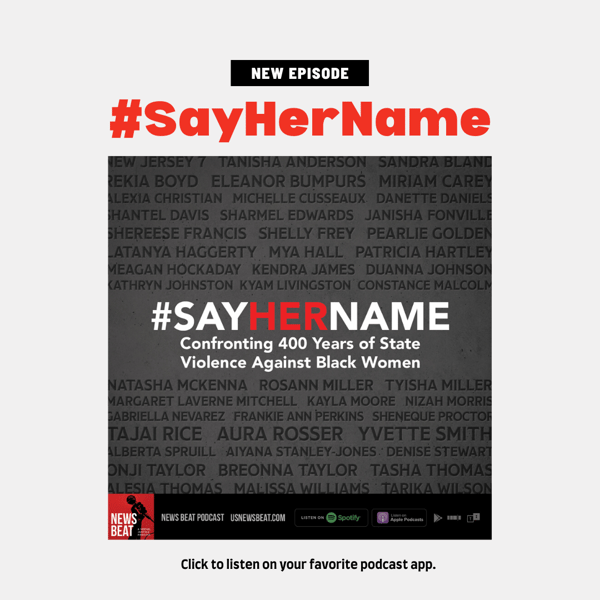

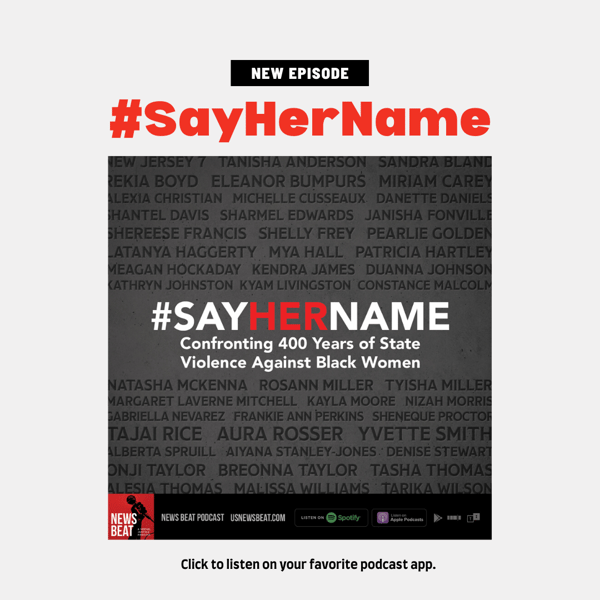

A seminal #SayHerNameReport by the social justice think tank African American Policy Forum (AAPF) and Center for Intersectionality and Social Policy Studies at Columbia Law School documents more than three dozen cases of Black women and girls killed or brutalized by police, yet you’d be hard pressed to hear many of their names chanted during the ongoing anti-racism rebellions. Advocates are in no way indicting the movement, of which they support, but instead attempting to shed a legacy of delegitimizing the lives of slain Black women, by bringing more attention to their plights.

As the most recent example, they point to the tragic death of 26-year-old Breonna Taylor, an EMT killed in a hail of police fire in Louisville, Kentucky on March 13. While those fighting for racial justice are not arguing for less coverage of Black men slaughtered by police, they note there’s a history of society ignoring physical and sexual violence directed at Black women throughout entire centuries, beginning with the transatlantic slave trade and continuing through today. Indeed, outrage over Taylor’s tragic death has fueled these protests, but it took months before her slaying manifested into collective fury.

Taylor’s death not only speaks to the modern-day struggle for justice but hundreds of years of state violence.

“There's never been a time in the entire United States history where Black women have not been violently assaulted both by the state as well as individuals,” says Michelle S. Jacobs, a professor of law at Levin College of Law at the University of Florida.

Consider the amount of broadcast news coverage generated in Floyd’s case as opposed to Taylor during the height of the 2020 uprisings. Floyd received eight times more mentions than Taylor between June 4 and June 29, according to the Internet Archive. Among the programs that referenced Taylor the most: the alternative news outlet Democracy Now!, the United Kingdom-based BBC, and C-SPAN, which mostly featured speeches by U.S. senators. Only one mainstream American outlet appeared in the top five: MSNBC.

Floyd’s death on May 25 was catapulted into the nation’s consciousness due to cellphone video that ricocheted across social media. Officer Derek Chauvin’s actions were considered so callous it provoked near-widespread condemnation.

On the other hand, Taylor was killed on March 13, and her death initially was framed in the context of seemingly mundane police raid interrupted by gunfire from someone inside her apartment. An early report made no mention of the cops shooting Taylor eight times after they stormed her apartment and woke her from her sleep. Fearing a home invasion, her boyfriend fired a weapon and was charged with attempted murder of a police officer. It wasn’t until two months later that the Courier-Journal reported Taylor was not the main subject of the drug probe.

That there was no video of her killing reinforces the notion that, in most cases, police violence toward women is rarely seen—and thus, rendered invisible, even. Taylor, months from turning 27, was yet another in a long list of female police victims—and very nearly forgotten.

#SayHerName

In 2015, protesters nationwide took to the streets following the killings of Michael Brown and Eric Garner, both unarmed Black men. That same year, AAPF released the #SayHerName report, “dedicated to Black women who have lost their lives to police violence, and to their families who must go on without them,” it states. Those named in the study range from a mere 7 years old to 93—a heart-wrenching reminder that violence befalls Black lives, regardless of age.

The broader #SayHerName campaign raises awareness about injustices targeting not only Black women but other marginalized groups, including transgender people. It also exposes pervasive sexual violence by cops, yet another under-reported aspect of American policing.

Andrea J. Ritchie, author of “Invisible No More: Police Violence Against Black Women and Women of Color” and co-author of the aforementioned #SayHerName report, tells News Beat podcast that Black women “are most likely to be killed by police when unarmed, of any demographic group.”

Research shows that police violence is one of the leading causes of death among young men in the United States, according to a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2019.

While the analysis found that Black men are more likely to be killed by police—at a rate of one in 1,000—it concludes Black women are also exposed disproportionately to such violence.

“Black women and men and American Indian and Alaska Native women and men are significantly more likely than white women and men to be killed by police,” according to the study.

The campaign to highlight this centuries-old violence directed at Black women comes amid a push to reform the entire criminal justice system.

As we’ve reported, the number of people locked up behind bars has increased 500 percent since the 1970s—a result of so-called “law and order” politics stoked by various U.S. presidents, the racist “War on Drugs” and the adoption of punitive sentencing measures. Between 1970 and 2014, women were the fastest-growing population of incarcerated people in the country, according to a 2016 report by the nonprofit Vera Institute of Justice. In four decades, the country went from having less than 8,000 women in jail in 1970 to almost 110,000 four decades later.

Jacobs, the University of Florida professor who specializes in critical race theory and women representation in the criminal justice system, argued in a comprehensive analysis published in 2017 that state violence against Black women is “pervasive.”

“Black women’s interaction with the state, through law enforcement, is marked by violence,” she wrote. “Black women are murdered by the police. They are assaulted and injured by the police. They are arrested unlawfully by the police; and finally they are tried, convicted and incarcerated for defending themselves against nonpoliceviolence. State violence against Black women is long-standing, pervasive, persistent, and multilayered, yet few legal actors seem to care about it.”

Simply providing an estimate of such deaths during even a narrow time period is difficult to nail down, because comprehensive data is virtually nonexistent, advocates say. As a result, the #SayHerName report was based largely on internet research and cases familiar to its authors. For the purposes of her article, Jacobs leveraged social media.

“The police...don't document when they're abusing Black men, so they're certainly not gonna document it when they're abusing Black women,” says Jacobs. “Social scientists don't study it, because they're not interested in it.”

“I had to go to social media to get the evidence of what was happening to Black women.”

Breonna Taylor’s Death

Taylor and her boyfriend, Kenneth Walker, were asleep when plainclothes Louisville police officers, just after midnight on March 13, executed a so-called “no-knock” warrant, using a battering ram to smash in to her apartment. Both Taylor and Walker were awakened by the noise. Walker, a legal gun owner, has said he didn’t know the men were cops and fired his weapon in self-defense, striking one of the intruders in the leg. The officers unleashed a hellfire of bullets, piercing Taylor eight times.

Walker frantically dialed 911. Clearly in shock, Walker explained to the operator that “someone kicked in the door and shot my girlfriend.”

The initial explanation provided by police stands in stark contrast to what we now know. A local news outlet reported that “when officers secured the home, they found a woman dead from the gunfire.” It made no mention that Taylor was fatally shot by the police, that she was struck eight times, or that officers executed a since-barred “no-knock” warrant.

“Officers knocked on the door several times and announced their presence as police who were there with a search warrant,” a police lieutenant said at a press conference on the day of Taylor’s death. “The officers forced entry into the exterior door and were immediately met by gunfire. Sgt. [Jon] Mattingly sustained a gunshot wound and returned fire.”

Walker and other witnesses dispute the department’s account that they knocked or announced themselves before entering the apartment.

A judge had approved a warrant to search the apartment as part of a drug investigation. Neither Taylor nor Walker had any prior history of drug crimes. The same night, the prime suspect had been arrested more than 10 miles from Taylor’s apartment, which authorities surmised was an address used by him to receive packages.

Prosecutors have since dismissed Walker’s charges and “no-knock” warrants have been outlawed by the city government under legislation called “Breonna’s Law.”

“That kind of situation where Black women are killed in the context of a ‘no-knock’ warrant during a drug raid is sadly very common,” says Ritchie.

A researcher-in-residence at Barnard Center for Research on Women, she rattles off a handful of similar cases, including the deaths of 92-year-old Kathryn Johnston and 7-year-old Aiyana Stanley-Jones.

In Johnston’s case, plainclothes Atlanta police officers executed a search warrant on Johnston’s home on Nov. 21, 2006 that federal prosecutors later revealed was based on false information, and ended with them planting marijuana inside her house as part of a cover-up.

Officers pried open the burglar bars Johnston installed for protection and rammed their way into her home. Startled and frightened, Johnston fired a single shot from a rusty revolver she owned in self-defense, but missed any of the intruding officers. They returned 39 shots, fatally striking the grandmother up to 19 times. All three officers involved pleaded guilty to federal charges for violating her civil rights and resulting in death, and two pleaded guilty to state voluntary manslaughter charges.

Stanley-Jones, asleep on the couch as her grandmother watched TV, also never had a chance.

A flash grenade crashed through the window and exploded as a Detroit police “Special Response Team” stormed their home. Officer Joseph Weekley, who led the unit that night, shot the 7-year-old in the head, killing her.

Outside, a crew for the reality TV series “First 48” was filming, raising questions about whether the unit was playing up for the cameras as they hunted a murder suspect.

Following the fatal May 16, 2010 shooting, Detroit police said the tragedy was an accident. First, they stated the gun went off when the girl’s grandmother grabbed it. Later, they claimed the grandmother brushed the gun as she ran, causing it to fire. The family said both accounts are untrue. Weekley, charged with manslaughter but never convicted, returned to the force five years later.

Ritchie knows far too many of these stories.

“I'm looking right now in my apartment at a poster that we made in 2015 with some colleagues that list 100 Black women and girls killed by police,” she says. “And there are 5-year-olds on this list.”

Sexual Violence By Police

On June 9, the Courier-Journal revealed yet another startling allegation regarding Breonna Taylor's gruesome slaying. One of the officers involved in the botched raid and fatal shooting was being investigated for multiple sexual assault accusations.

The incidents, shared on social media, share striking similarities. In one, a woman wrote on Facebook that she went drinking with friends and Det. Brett Hankinson offered her a ride home.

"He drove me home in uniform, in his marked car, invited himself into my apartment and sexually assaulted me while I was unconscious,” she posted, adding that “fear of retaliation” caused her not to report the incident.

A second woman shared a similar story on Instagram: Walking home from a bar, Hankinson drove up and offered her a ride home.

“He began making sexual advances towards me; rubbing my thigh, kissing my forehead, and calling me 'baby,’” she wrote, adding that she ran after he pulled up to her apartment building. She said a friend reported the incident.

Ritchie says sexual violence by law enforcement is the “second-most frequently reported form of ‘police misconduct’ after excessive force,” but “certainly not the second-most frequently talked about.”

She cited a study published in 2015 that examined a decade’s worth of information and found that an officer is accused of sexual misconduct every five days.

“The vast majority of incidents, the report found, involve motorists, young people in job-shadowing programs, students, victims of violence and informants," Ritchie wrote in a Washington Post piece. "In more than 60 percent of the cases reviewed, an officer was convicted of a crime or faced other consequences.”

Despite the frequency of such attacks, Ritchie reported that half the police departments in the nation don’t have a written policy prohibiting sexual harassment of members of the public.

In her book “Invisible No More,” Ritchie writes of several incidents in which police respond to calls of a missing girl and officers tell helpless family members their searches are contingent on sexual favors. She also found similar complaints of cops hitting on domestic violence or sexual assault victims.

“There's just documented statements from police officers that that's actually something they do with awareness and intention,” Ritchie says.

"They say, ‘Yeah, if I'm going to show up as a knight in shining armor to save someone from a domestic violence situation, of course, I'm going to ask her out on a date,'" she continues, adding that one cop likened such behavior to "shooting fish in a barrel.'"

She recalls another incident in which an officer said: “The badge gets you the pussy and the pussy gets you the badge.”

In her WaPo piece, Ritchie writes: “These cases are unique only in that the officers faced consequences for their actions. Accountability is rare. One study found that in 41 percent of cases, officers charged with sexual violence had been previously accused of sexual misconduct—between two and 21 prior allegations—but had remained on the force. Even when officers are terminated or allowed to resign, many are able to simply move on to another department, in what researchers dub the ‘officer shuffle.’”

In speaking of Taylor’s case, Ritchie said, through her research, she’s found that sexual misconduct “is often a precursor to physical and fatal violence.”

Hankinson has since been fired for his role in Taylor’s death. To date, no one involved has been charged.

Activists continue to demand justice for Taylor and other female police-slaying victims. Meanwhile, the #SayHerName campaign continues to shine a light on those who've suffered harm from those sworn to protect, with the goal for a nation steeped in racism to finally proclaim "Black Women’s Lives Matter."