When hundreds of thousands of youth protesters mobilized last summer for a

historic climate strike, many highlighted the disproportionate impact the crisis is having on minority communities.

“We can't separate [climate change] from the communities of color, low-income communities that are going to have to deal with the financial consequences of this,” one Boston-based organizer for the youth-driven climate group Sunrise Movement told News Beat podcast at the time.

Minority communities in the United States are historically underserved, overpoliced, and receive significantly less in school funding. Making matters worse, many of these neighborhoods are located closer to industrial plants and major highways, creating unequal exposure to pollutants.

For countless neighborhoods, racist policies that emerged decades earlier have not only persisted but are contributing to the increasing perils associated with human-caused climate change.

In fact, the areas victimized by racist federal housing policies in the 1930s are now among the most vulnerable to the severe impacts of climate change, according to a landmark study released in January by researchers at Portland State University, the Science Museum of Virginia, and the Center for Environmental Studies at Virginia Commonwealth University.

And although the Fair Housing Act of 1968 banned redlining and housing discrimination in general, three out of four redlined communities rated "hazardous" 80 years ago are struggling economically today.

“Our results reveal that 94 percent of studied areas display consistent city-scale patterns of elevated land surface temperatures in formerly redlined areas relative to their non-redlined neighbors by as much as 7-degree Celsius,” researchers wrote.

Drawing from maps used by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, created by the federal government in the 1930s to identify credit-worthy communities, researchers for the first time determined that areas once deemed “hazardous” are disproportionately exposed to extreme heat.

Underscoring the severity of the problem, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says heat kills more people than any other hazardous weather event, and deaths are expected to increase as warming continues.

Additionally, multiple studies have linked race and poverty, among other socio-demographic factors, with higher risks for extreme heat exposure, including one such examination of heat wave deaths in New York City. Published in Environmental Health Perspectives, a peer-reviewed journal, the 2015 study found that black residents were more likely to die than people of other ethnic groups.

"Indeed," its authors wrote, "we also found that living in neighborhoods that received more public assistance was associated with a higher likelihood of dying during a heat wave."

“When we talk about heat exposure, it's these communities that have been in these places for decades that are now facing some of the most acute and highest temperatures in any of our cities,” Vivek Shandas, professor of urban studies and planning at Portland State University and one of the researchers behind the study, tells News Beat podcast.

“In many ways,” Shandas adds, “if the planet is getting warmer and we're seeing more frequent, more intense, and longer duration heat waves, then in many ways we are encountering what I would call a public health crisis.”

The unsettling findings come amid warnings that the planet has warmed 1°C above pre-industrial levels and that leaders have about 11 years to limit warming by another half-degree Celsius to prevent irreversible and catastrophic changes.

In many ways, communities throughout the United States, especially those that have been marginalized, can’t wait any longer.

Nineteen of the 20 warmest years on record have occurred since 2001, with 2016 being the warmest. Major cities are typically warmer than their surrounding areas as a result of the so-called “urban heat island effect.” However, as Shandas and his colleagues have revealed, heat levels can vary depending on where you live in a particular city—and that area’s credit designation 90 years ago.

On average, formerly redlined communities are 2.6°C, or 5°F, warmer than those graded more favorably, according to the study. Overall, it examined 108 cities and found that the temperature disparity was as high as 12°F, with the greatest temperature differences in the Southeast and western cities.

“If you'd asked me if there had been a relationship between risk-based housing segregation and the redlining maps and vulnerability to extreme heat, I probably would have said ‘Yes, it's one of those things, it's disappointing but not surprising,’” says Cate Mingoya, director of capacity building at Groundwork USA, an environmental justice group that oversees 20 grassroots organizations across the country.

“But I never would have thought it would have been as [an] extreme connection.”

Redlining & Housing Discrimination

Redlining returned to the American mainstream this winter after a recording emerged of the billionaire and short-lived Democratic nominee for president Michael Bloomberg blaming the 2008 financial crisis on bans to housing discrimination.

The former mayor of New York City was widely condemned for his remarks, which were first reported by the Associated Press. Bloomberg failed to mention that the federal policy was decidedly racist and prevented generations of Americans from accumulating wealth. And as mayor of New York City, Bloomberg would theoretically know all about redlining, as all five boroughs were rated by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC).

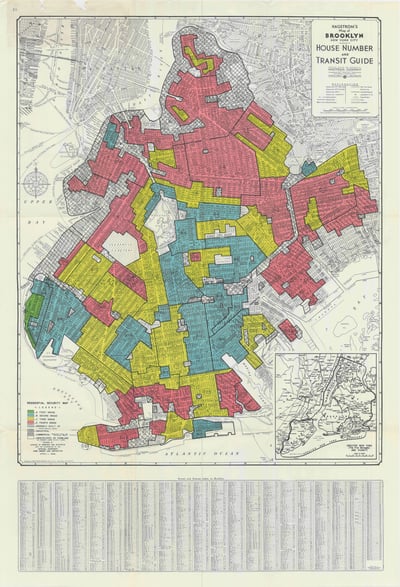

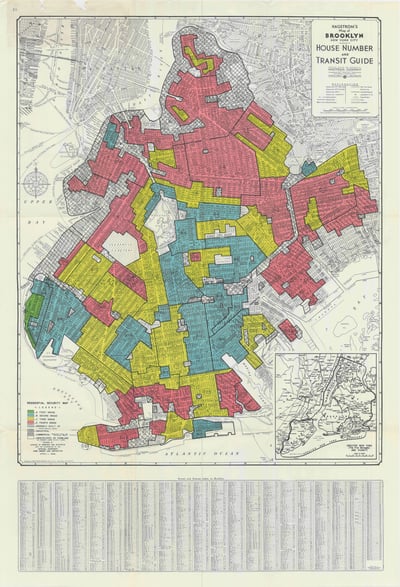

(Caption: Scan of an Home Owners' Loan Corporation map of Brooklyn, NY. Photo credit: University of Richmond)

As the United States was rebuilding its economy following the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt instituted a series of public programs to jump start the economy. In 1933, the federal government founded the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, which was charged with creating residential security maps to support federally backed mortgages.

“What the federal government did was it sent out examiners to about 200 to 250 cities throughout the United States to formally look at neighborhoods within those cities and determine what their creditworthiness was,” says Bruce Mitchell, senior research analyst at the fair housing nonprofit National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC). “And they had this very defined grading scale.”

Neighborhoods fell into four color-coded categories: The "best" were shaded green, and "still desirable" were blue. Meanwhile, "definitely declining" neighborhoods were designated yellow and the most “hazardous” were coded in red—thus the term “redlining.”

“Generally,” says Mingoya, “the areas that were outlined in green or ‘greenlined’ were white areas” with higher quality housing stock.

“The areas that were redlined were people of color,” she adds. “So black folks, extremely, extremely low-income folks.”

As Mangoya explains, “definitions of whiteness have changed over time,” adding that notes written on HLC maps “differentiate the right and wrong kind of white people, the right kind of French, the wrong kind of French.” But for the most part, redlined areas were predominantly home to black Americans.

The NCRC released a study in 2018 that found the economic struggles facing formerly redlined communities persist today.

“Today, 65 percent of ‘majority-minority’ communities are still in neighborhoods graded ‘hazardous’ in the 1930s and colored red on HOLC maps,” the study found. “In these neighborhoods, credit, the lynchpin of economic mobility, became either unavailable or very expensive. In contrast, neighborhoods given the highest grade in the 1930s, marked in green, are today 91 percent upper income, and almost entirely white.”

The NCRC’s Mitchell says these areas were deprived of capital, which made it incredibly difficult to improve the housing structure, or for minority groups to start businesses. Today, more than 80 percent of businesses with employees are white-owned, with blacks and Hispanic shares only at about 3 and 6 percent, respectively, Mitchell adds.

“Say you're a homeowner of color, you're stuck there, you can't buy and you can't sell because no one else is able to get that debt to secure that property, which means that there's lower investment in your community,” says Mangoya. “I saw a lot of abandonment of buildings and slums pop up related to that redlining period.

“The other thing that's really frustrating about this,” she continues, “is that it's not just up to these communities that are suffering most in the climate crisis to find the mitigation measures. It's also up to them to convince people that there's a problem and that what happened in the 1930s is still relevant today.”

Redlining & Dangers Of Climate Change

Groundwork USA operates a project called Climate Safe Neighborhoods that includes five “trusts” spread out across the country, in: Denver, Co.; Richmond, Va.; Elizabeth, N.J.; Pawtucket and Central Falls, R.I.; and Richmond, Ca.

Each trust organizes and builds relationships with local stakeholders to make communities more resilient to extreme heat and flooding.

While planting trees and installing so-called “white roofs” to protect against rising temperatures are among each community’s top priorities, organizers also educate people on how systemic racism crippled these neighborhoods and exposed them to extreme heat and other hazardous weather events.

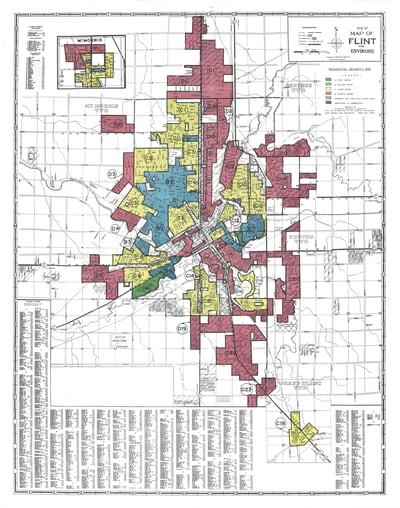

(Caption: Scan of an Home Owners' Loan Corporation map of Flint, Michigan. Photo credit: University of Richmond)

(Caption: Scan of an Home Owners' Loan Corporation map of Flint, Michigan. Photo credit: University of Richmond)

Mangoya acknowledges that on one level it’s wholly unfair that today’s residents are responsible for righting a decades-old wrong. But with so much at stake, their collective energy is better spent building toward a better future.

“One of the things that's nice about this process too is we're pulling in a broad array of allies to help, not just help the community identify and prioritize their mitigation measures, but help to do that legwork of convincing folks that ‘Yeah, this is a problem and it needs to be rectified,’” she says.

There’s little time to waste.

According to the CDC, children, pregnant women and seniors older than 65 are most at risk of extreme heat. City dwellers experience warmer days due to the aforementioned urban heat island effect, which the agency blames on a lack of shade, heat-absorbing conventional roofs, and reduced airflow resulting from a combination of tall buildings and narrow streets.

“All these factors contribute to urban heat islands, which can worsen the impacts of climate change, particularly as more extreme heat events occur,” according to a guidebook developed by the CDC and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). “Compared with surrounding rural areas, urban heat islands have higher daytime maximum temperatures and less nighttime cooling.”

“Temperatures in urban areas can be 1.8–5.4°F warmer than their surroundings during the day,” the guidebook adds. “In the evening, this difference can be as high as 22°F because the built environment retains heat absorbed during the day.”

Shandas, the Portland State University professor and co-author of the report analyzing the impact of climate change and redlining, refers to heat as an “insidious kind of natural hazard.”

“Really what it comes down to is how our bodies are able to cope with that particular heat that we're feeling on our skin,” he tells News Beat podcast.

Generally, he says, human sweat evaporates and creates a cooling effect on our skin when it becomes too hot. Even that biological correction could suffer.

“What we see from the research point of view is this phenomenon called wet-bulb temperatures,” says Shandas. “And that is when we're actually not seeing evaporation happen from the skin and our bodies are actually not able to cool down.”

Historically, he adds, humans react well to temperatures around 70 degrees. But if people in segregated communities are exposed to temperatures at or exceeding 98.6 degrees, it may make it increasingly difficult to cool off from the ambient environment—and the outcomes could be deadly.

That was made clear by a 2018 Portland State University study, published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, that concluded impoverished, non-white residents of Portlan, Ore., "are at higher risk for heat exposure."

“Those that have pre-existing health conditions, older adults, those that are aren't able to find cooling resources, whether it be air conditioning, whether it be a cooling center in your local neighborhood, those are the folks we've seen systematically die and have a lot of excess mortality and morbidity—that's disease and death—beyond what we would regularly see when these heat waves come through,” Shandas explains.

In a perfect world, the federal government would get involved and potentially direct funds to support community-level mitigation efforts. Shandas has no illusions that would happen, however.

As a presidential candidate, Donald Trump characterized climate change as a Chinese-manifested “hoax.” As president, his administration has reduced the role of science, and according to a New York Times tally, rolled back or threatened to diminish at least 95 environmental regulations. In one of the administration's most significant policy moves to date, it announced last November that the United States would formally withdraw from the historic Paris climate accord in the fall of 2020.

If Shandas had a wish list to address the crisis, it would appear something like this: Lawmakers would acknowledge that an injustice was done, start moving to reduce the disproportionate effects of climate change, and identify ways to cool historically underserved communities. He suggests the latter could be done through outreach during heat waves, tree planting, and building more green spaces.

“We want to find ways to advance climate-friendly housing that allows communities to stay cool and stay free from floods and landslides and a lot of the acute stressors that climate change brings,” Shandas says.

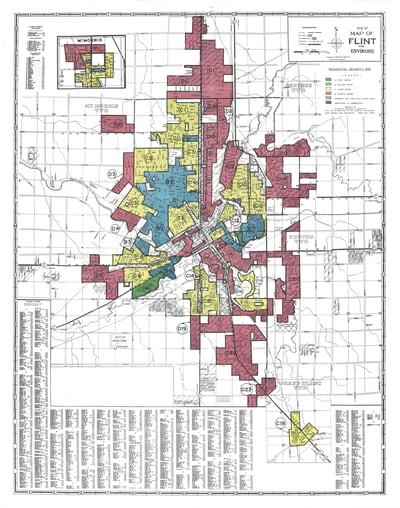

(Caption: Scan of an Home Owners' Loan Corporation map of Flint, Michigan. Photo credit:

(Caption: Scan of an Home Owners' Loan Corporation map of Flint, Michigan. Photo credit: