Boudin was only 14 months old when his Weather Underground activist parents were arrested. That night, the Boudins left the infant with a babysitter and participated in an armed robbery that killed three people, including two police officers.

Years later, Boudin became a deputy public defender in San Francisco, devoting his life to the accused—the very people the district attorney’s office is responsible to prosecute.

Boudin, a Rhodes scholar and Yale graduate, points to both experiences when trying to convince voters that he’s the most qualified candidate for the job.

The 39-year-old’s candidacy adds to the uniqueness that is the race to become San Francisco’s next district attorney. It is the first open competition for the office in more than 100 years. Adding to the intrigue, the city’s mayor, London Breed, appointed Suzy Loftus, one of the other three candidates in the race, as interim DA, igniting a political firestorm with less than a month until the election. (Breed endorsed Loftus earlier in the campaign.)

The four-way race only became possible after the city’s district attorney said he wouldn’t seek re-election.

If he succeeds, Boudin would only have his mother, Kathy Boudin, around to congratulate him. Both his parents were charged under New York’s felony murder rule for driving the getaway car during the infamous robbery. Kathy Boudin served 22 years and was released in 2003 while Boudin’s father, David Gilbert, is serving a sentence of 75 years to life.

Just as other reform candidates across the United States have had lofty ambitions, Boudin hopes to dramatically reconfigure the justice system in San Francisco—a city home to immense wealth but where 10 percent of residents live in poverty.

Among his proposals: eliminate money bail, prosecute police misconduct and protect immigrants from ICE, expand mental health services, and ultimately, end mass incarceration.

Boudin doesn’t want to stop there.

One of his more ambitious proposals calls for a “restorative justice” program that would potentially allow people to bypass courts altogether—a philosophy that is seemingly anathema to the modern perception of “justice.”

Restorative justice gives victims the choice about how to proceed: either through the traditional judicial process or by engaging with the person who harmed them in a supervised setting. Its proponents argue that the perpetrator is still held accountable because they have to reconcile with the pain they caused, something that rarely happens during court proceedings or during incarceration.

This approach is not as innovative as it may seem. Restorative justice has its roots in indigenous traditions that predate the modern penal system. While commonly used by community-based groups, it’s become a useful mediation tool for public agencies, including law enforcement and schools.

THE COMMON JUSTICE MODEL

Boudin’s proposal is partly inspired by one such organization in Brooklyn called Common Justice. Its office abuts immigrant-operated shops one block from a bustling subway and rail terminal, where people of all races, genders, and creeds converge before going their own way.

Common Justice, too, brings people together under one roof before they embark on their own journeys.

Danielle Sered, executive director of Common Justice and the organization’s founder, says they develop and advance solutions to violence to meet the needs of those who are harmed.

Common Justice distinguishes itself from other restorative justice programs by confronting serious violence—crimes that account for almost 50 percent of prison sentences in the country.

“We have this myth as a country that we’ve done mass incarceration in crime victims names,” Sered tells News Beat podcast. “It is true that politicians have invoked crime victims, in almost all of their efforts to impose draconian sentences, whether that’s an individual case or as a matter of policy.

“It is true that some crime victims have asked for those draconian sentences,” she continues. “Those kinds of victims are actually, for the most part, the outliers. In some ways, I think the most interesting thing we’ve learned at Common Justice is about what crime survivors want.”

Studies have shown that nearly half of the victims of violent crime don’t report such incidents to police. Of the survivors that Common Justice reaches out to, 90 percent choose restorative justice over incarceration for the person who harmed them, Sered says.

“It’s a wild number,” she adds.

“At the end of the day, there are two things crime survivors can’t abide. We can’t abide the thought of going through what we went through again. And we can’t abide the thought of someone else going through what we went through,” Sered explains. “So if we’re faced with a choice, between two options to address the pain we’ve experienced, whatever we feel, whatever rage, whatever vengeance we want, we will choose the thing that we think produces safety.”

Common Justice’s cases originate from the Brooklyn and Bronx District Attorneys’ offices, either from defense attorneys or survivors themselves. Common Justice works directly with officials from each office and obtains their consent to divert those cases.

Each party sits around a circle and is only permitted to speak when they’re holding a talking stick. The circle includes a trained facilitator, two people who are separately assigned to the survivor and the person who caused harm and additional support personnel. The feelings are raw and the wounds gaping.

“I think very often the stories we tell about restorative justice really center on this process of forgiveness and relationship,” Sered says. “Those things are beautiful when they occur. The thing that has to occur is repair. And sometimes that is not actually about forgiveness. And sometimes it’s not fundamentally about relationship. It’s about a process of making things right, of mending the rip in the social fabric that the crime opened up.”

“And I think part of why it’s really important that we understand that is that when people think about whether restorative justice could be a good solution to something they worry about experiencing or that they have experienced, very often the question they ask themselves is ‘Could I forgive that person?’ I don’t think that’s the right question. The question is, ‘What does repair look like to me? And could this process deliver it?’”

Rachel Barkow is a law professor and faculty director at NYU’s Center on the Administration of Criminal Law and the author of “Prisoners of Politics: Breaking the Cycle of Mass Incarceration,” released this year. Alternatives to incarceration, says Barkow, are a “very promising space to think about how we want to address crimes that involve violence.”

While she considers restorative justice to be a benefit, Barkow has concerns about scalability—especially as a solution to ending mass incarceration in the US, where more than 2.2 million people are either in jail or prison.

“If we’re talking about roughly half of the prison population in there for a crime of violence, that means that they would need to be able to handle about a million people,” Barkow tells News Beat podcast from her office at NYU. “And so thinking about how you’re going to move that model to a million people is not easy, you know? So I think that’s the big question mark for that model. But I think it’s worth thinking about how to do it, for sure. And I think it’s also worth thinking about…where is it most efficient to use it?”

Barkow notes that the current system—at all levels, from the federal system on down—largely doesn’t do enough to help people who are incarcerated.

“I think the public probably doesn’t know that 10,000 people come out of jails and prisons every week in America,” she says. “So that’s 10,000 people rejoining, so you’d want them to be kind of ready to really reenter successfully and not commit whatever offense they did in the first place. And I think restorative justice thinks about those kinds of things, really thinks about how do we make somebody…think about what they did, and reflect upon it.”

BOUDIN’S TEST

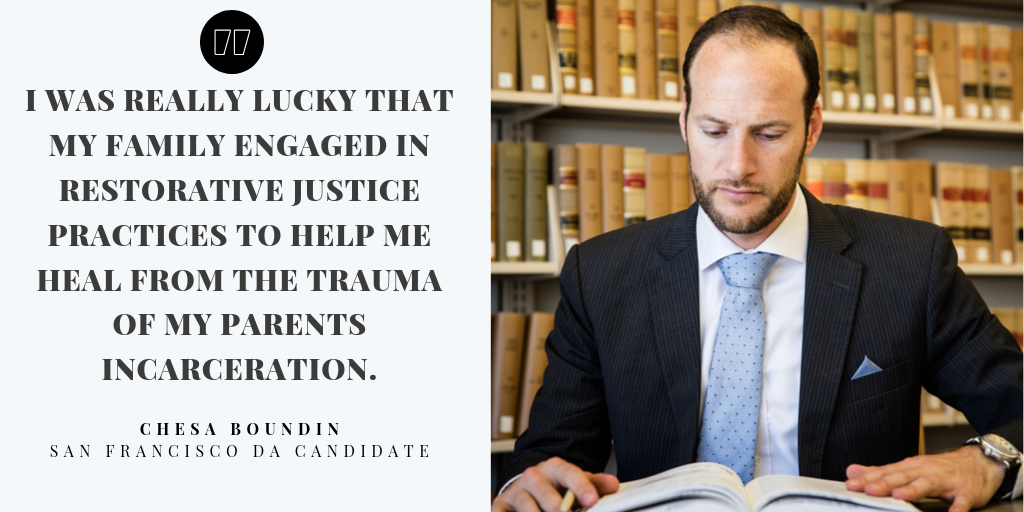

Most political candidates avoid discussing personal or familiar indiscretions. Running as a reformer, Boudin has made the tragedy the centerpiece of his campaign, underscoring how the trauma informs his candidacy. He also remembers participating in restorative justice himself which ultimately helped him heal from the trauma of having incarcerated parents and forgive them.

“Years of prison visits taught me hard lessons about how broken our criminal justice system is,” he tells News Beat podcast. “About how broken it is for the people who commit crimes and are not rehabilitated or held accountable in a way that allows them to heal the harm they’ve caused. How broken it is for victims of crime, who have so little to show for the billions of dollars that we spend on mass incarceration.”

Boudin realizes his restorative justice plan is an ambitious one.

He says the basic premise is to give “every victim of every crime in San Francisco the right to participate in restorative justice if they choose to, it doesn’t matter how serious or how minor the offense.”

“But the goal is to focus on healing the harm that the victim suffered, and to require the person who caused that harm to lead the way in doing that,” he adds.

His campaign has not committed to eliminating jail or prison as a possibility—a clear distinction as compared to other restorative justice programs. Boudin wants to be as inclusive as possible and he admits that many people may not be familiar with the process and it may take time to implement fully. But his hope is that after his first four-year term, if elected, that it becomes a national model.

“I think in the short term, the goal is to have as many people participate as possible, and to use it to heal the harm victims have suffered and to reduce, where we can’t eliminate, jail and prison as part of the punishment,” he says.