But to the people who experienced large-scale protests in the late 1960s in black communities across the United States, there’s only one way to adequately describe these tsunamis of raw, visceral, outrage that shook America to its core: “Rebellion.”

Like a slow-churning hurricane steadily absorbing energy before violently making landfall, the long-simmering grievances that festered in black communities since their founding funneled into one massive superstorm, unleashing wave after wave of galvanized public dissent and resistance. For many cities across the United States, the dams were no match for the sheer force of the people.

The final straw came on April 4, 1968, when Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tenn.

At an event in Indianapolis in which Robert F. Kennedy was speaking to supporters, he politely requested the audience lower signs they had been holding. The crowd was slow to recognize the urgency in his voice.

“I have very some very sad news for all of you,” Kennedy said, before sharing reports of the iconic preacher’s violent death. The audience shrieked in horror, as if they were witnessing King’s demise with their own eyes. Their guttural cries were so intense that it seemed to open a portal into their collective hearts—rupturing with each thunderous wail.

Imagine this emotional upheaval reverberating through community after community, particularly those largely comprised of African Americans, in cities devastated by poverty, high rates of unemployment, discrimination, police brutality, and overall political disenfranchisement. Millions of hearts broken—all at once. The man who had spoken for an entire race was gone, felled by an assassin’s bullet. His dream—their dream—not only deferred, but seemingly snuffed out entirely.

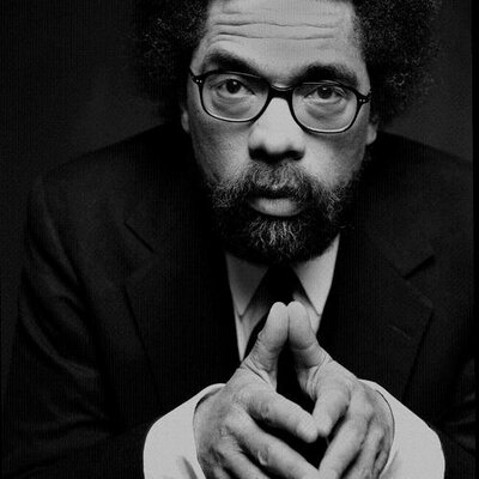

“The killing of Martin, it was just too much. You couldn’t take it anymore,” famed intellectual Dr. Cornel West tells News Beat podcast. “Something snapped inside of all of us.”

With little recourse to be had, many politically marooned communities engaged in active rebellion against the powers that be.

From Baltimore, Cincinnati and Washington, D.C. to Chicago, Kansas City and Detroit, raw emotion spilled into the streets. The reaction was so profound that state officials mobilized the National Guard to help quell the unrest. In Wilmington, Del., which experienced small-scale riots in comparison to other major cities, the National Guard stayed in place for nine months, transforming the city into a virtual police state under siege.

West, professor of Public Philosophy at Harvard University, counts “over 150 mass rebellions” in the United States after King’s death.

In reaction to negative outcomes, public officials often lament the absence of “hindsight” when defending their response. In the case of the post-King rebellions, there was no need for soul-searching. In the year prior to King’s death there was just as many demonstrations as there were after his murder, according to Larry Hamm, chairman of People’s Organization for Progress, a grassroots social-justice group based in Newark.

In a speech to the nation on July 27, 1967, President Lyndon B. Johnson spoke about the tumult in city streets across the country.

“My fellow Americans, we have endured a week such as no nation should live through, a time of violence, and tragedy,” he said. Johnson said he’d convene a special commission, led by Illinois Gov. Otto Kerner, to analyze the “origins of the recent disorders in our cities.” The FBI, Johnson noted, would embark on a criminal investigation to “search for evidence of conspiracy.”

Remarkably, this all preceded King’s death. During the 1967 Newark rebellion, for example, demonstrators flocked to the streets in response to the arrest of a black cab driver named John Smith. Also contributing to the unease were rumors that Smith had been killed by the authorities. That the gossip was erroneous was in some ways insignificant. What mattered above all else were the previous cases of police brutality from inside the very precinct where Smith had been taken. It wasn’t the first time people had heard rumors of someone being beaten, or worse, dying, inside that precinct.

What took hold after King’s death was a cumulative, collective reaction to rampant injustices in black communities, with demonstrations breaking out in dozens of cities. In Baltimore, it took about two days for tensions to boil over. Fires were set and looting occurred in about 15 different business districts across the city, says Elizabeth Nix, assistant professor and chair of the Division of Legal, Ethical and Historical Studies at University of Baltimore, who co-authored an anthology titled “Baltimore ’68: Riots and Rebirth in an American City.”

Baltimore sustained $12 million in damages. A half-dozen people were killed in the unrest. More than 5,000 people were arrested in a three-day span, mostly for violating curfew, Nix says.

Nearly 50 years later, Baltimore would once again become the scene of one of the most significant civil disruptions in modern history following the death of 25-year-old Freddie Gray while in police custody. Seared into people’s minds was the scene of an engulfed CVS. The reaction from observers ran the gamut, ranging from ignorance, legitimate confusion, and righteous indignation: “Why are these people burning down their own neighborhoods?” became the prevailing question.

Forgetting for a second that the people in the Baltimore did not collectively “own” the CVS that went ablaze, there’s psychological reasons why people damage property near their homes, Nix explains. In 1968, she says, there was a perception that some businesses treated people unfairly or disrespectfully. White-owned banks would not lend money to black people, for example. Similarly, credit was not afforded to black people. In 2015, one of the storefronts targeted was a check-cashing business on Fulton Avenue known for imposing high-interest rates.

“Riots,” as the media so often describe these open rebellions, occur for many reasons, explain those interviewed for this podcast and story. In Baltimore, it was Gray’s death, combined with a history of racial inequality. In Ferguson, it was the death of 18-year-old Michael Brown, and an overall perception that blacks were disproportionately targeted by officers conducting traffic stops, among other issues.

The violent protests in Ferguson triggered a Department of Justice review of police practices revealing an overzealous law enforcement strategy that put a premium on revenue from tickets and other infractions to help fund city government. African Americans, the DOJ found, were the group that suffered the most.

This emphasis on revenue has “compromised the institutional character of Ferguson’s police department, contributing to a pattern of unconstitutional policing, and has also shaped its municipal court, leading to procedures that raise due process concerns and inflict unnecessary harm on members of the Ferguson community,” the report states.

“Further, Ferguson’s police and municipal court practices both reflect and exacerbate existing racial bias, including racial stereotypes,” it continued. “Ferguson’s own data establish clear racial disparities that adversely impact African Americans. The evidence shows that discriminatory intent is part of the reason for these disparities. Over time, Ferguson’s police and municipal court practices have sown deep mistrust between parts of the community and the police department, undermining law enforcement legitimacy among African Americans in particular.”

The dramatic and often violent demonstrations that have broken out in recent years are not unlike those of the past, with the combination of police violence and pent up anger igniting cities to explode.

“There were a lot of other issues that were logs on that fire,” Hamm, the community organizer, recalls. “And you could kind of say that Smith was the straw that broke the camel’s back. Smith was the spark that ignited the dynamite. Police brutality had been a long-standing issue in Newark, as it was in other cities across the country.”

Replace “Smith” with Garner, Castile, Brown, Martin, and Gray—all men killed by police—and what you have are the symptoms of a plague unleashed upon black communities: institutionalized inequality, racism and oppression. Like all diseases that go untreated, it has continued to spread unabated while beleaguered neighborhoods desperately cry out for help, or worse, completely lose trust in the system altogether.

“That history starts the moment there was a European who took an African, and that African fought back,” renowned activist, lecturer, community organizer and journalist Rosa Clemente tells News Beat podcast. “We’re always going to have civil disobedience, because people are going to get tired and are going to rise up, they’re going to rebel. That’s the United States’ history, period.”

‘WE DON’T CALL IT A RIOT’

Hamm was only 13 when Newark became the scene of a violent uprising.

“I had no idea this was coming,” says Hamm, recalling those defining days of his youth.

Hamm’s family was not politically conscious at the time. They had told him stories of black oppression, but these were shared by many families, especially among those who’d escaped the historically oppressive South.

Hamm’s father passed away when he was only 4. His mother was a seamstress at the dry cleaners around the corner from their apartment, which he and his mother shared with his grandparents. His grandfather was a boiler man.

Hamm was with a friend across the street the day Newark revolted. Somebody ran upstairs and told them, “Springfield Avenue is on fire.”

“We lived in a three-family, wooden-frame house,” Hamm tells News Beat podcast. “We had a front porch, we lived on the second floor. And we sat out on the porch and we watched this thing unfold.”

After the initial night of unrest, the rebellion spread across Newark. Springfield Avenue is the major roadway that connects the outskirts of the city with downtown.

From his porch, Hamm watched as looters overran businesses and claimed goods for themselves. As tensions escalated, Newark Police became more active. Still, the small, 15-member force was severely outnumbered. In response, the governor declared a state of emergency, and 700 state troopers and about 1,500 members of the National Guard were deployed to restore order.

For a teenager who had just graduated the eighth grade, Hamm wasn’t able to distinguish between National Guard troops and the military. For all he knew, the U.S. Army was sent to his city to clamp down on the unrest. As demonstrations continued, the National Guard resembled something akin to an occupying force. Heavily armored vehicles droned through the streets. Flanks of armed soldiers marched by. There were the chilling snaps of repeated gunfire. The military established checkpoints across the city. A curfew was imposed. The city itself came to symbolize a national dilemma: a government trying to maintain order, by whatever means possible, and its citizens openly rebelling against institutionalized oppression.

“You had the police, local police, the state police, and the National Guard working in tandem to try and put down this rebellion,” Hamm explains. “That’s how you know you have a rebellion. If you call in the Army, you know it’s obviously not a riot. A riot is something that happens after a football game or a soccer game, and the police can take care of it and handle it or whatever. If you have to declare Marshall Law, if you have to declare a state of emergency, and within the state of emergency you declare Marshall Law, you set curfews and you send in the Army, obviously there’s an uprising taking place. And Newark wasn’t the first. Nor was it the only one.”

Similar scenes played out in almost every major city in New Jersey between 1966 and 1967. There were also simultaneous rebellions taking hold, as in the case of Newark and Plainfield, its sister city to the west.

At least 26 people were killed in Newark during the four days of intense protests. Hamm still remembers the smell of charred buildings in the air. The stench hung around for weeks. Broken glass crunched under his feet as he walked across Springfield Avenue, the city’s shopping district, in the following days.

Hamm surveyed the damage. As an innocent teenager who had just literally witnessed his city burn, a curious thought crossed his mind: Would school reopen in September?

WAVES OF MUTILATION

Ignited by the shocking slaying of Martin Luther King, Jr., mass demonstrations broke out across the nation in 1968.

“Martin Luther King dedicated his life to love and to justice for his fellow human beings, and he died because of that effort,” Robert F. Kennedy told the shocked faces in Indianapolis.

“In this difficult day, in this difficult time for the United States, it is perhaps well to ask what kind of a nation we are and what direction we want to move in,” Kennedy continued. “For those of you who are black—considering the evidence there evidently is that there were white people who were responsible—you can be filled with bitterness, with hatred, and a desire for revenge. We can move in that direction as a country, in great polarization—black people amongst black, white people amongst white, filled with hatred toward one another.”

“Or we can make an effort, as Martin Luther King did, to understand and to comprehend, and to replace that violence, that stain of bloodshed that has spread across our land, with an effort to understand with compassion and love.”

Despite calls for calm, those who revered King, and others who simply followed his rise with approving nods, couldn’t help but feel outraged. As West says, something “snapped.”

News reports from the day of King’s death note almost immediate violence in Memphis, where he was gunned down.

Baltimore was among the many cities to revolt after the iconic preacher’s assassination.

To this day, the demonstrations of ’68 in Baltimore are fraught with misperceptions. One of the most predominant, says Nix, the professor, centers around the argument that people moved in droves as a result.

In reality, white, middle-class Baltimore City residents had been leaving since the 1940s, she explains.

It is true that Baltimore suffered the most unrest and the highest amount of financial damage, second only to Washington, D.C. However, Nix tells News Beat podcast: “The myth was that lots of retail establishments had shut down after the unrest. And what we found was that, in fact, a lot of retail establishments hung on and they reopened very soon after the unrest, and actually advertised in newspapers and said, ‘You may think that Lombard Street burned down, but in fact we’re open for business, please come back.’”

“The loss of retail in Baltimore city we can attribute more to natural loss of retail that happened in a lot of Rust Belt cities across the nation,” she continues. “A lot of those businesses held on until the 1970s, and closed for other reasons, and not just because of that unrest.”

While one of the predominant igniters of the demonstrations in 2015 was Gray’s mysterious death inside a police van, it was King’s stunning murder in 1968 that motivated people to flood the streets. But as is the case with most instances of mass protests, there were myriad underlying issues that came to fore.

“Everyone realized that neighborhoods that experienced disinvestment were getting very frustrated because you had the great society, Lyndon B. Johnson’s efforts to put more money into the inner city, to open up housing opportunities, to make it so that people wouldn’t be restricted in racially segregated neighborhoods as they had been,” Nix says. “But that change was slow and coming, and so a lot of people thought there was a loss of hope.”

As part of a collaborative project called “Baltimore ’68: Riots and Rebirth,” Nix and her students sought to better understand the reasons for the unrest. They interviewed more than 70 residents in Baltimore City, including a pastor who noted that there was hope that the “disturbance,” which he called it, would help transform disinvested communities for the better.

Rebellions, or “riots,” are almost universally discredited by the very institutions that the people are raging against. It is true that King rejected “riots” as a mechanism to exact change, but he clearly understood why such forms of resistance take form.

Indeed, King famously referred to “riots” as the “language of the unheard.”

As is evident over and over throughout the archived history of such violent outbursts—whether written, oral, or the endless hours of TV footage now easily accessible on YouTube—officials in powerful positions nearly always publicly lament them while simultaneously promoting King’s legacy of peaceful protest. Yet they often fail to see, or at least acknowledge, why such visceral demonstrations happen in the first place.

Cases in point: When Johnson took to the airwaves in 1967 in response to the sweeping unrest across the country, he also called on the FBI to investigate whether a criminal conspiracy was to blame. In Baltimore in 1968, officials talked about the need to restore “law and order” by confronting “force with force.” In 1992, President George H.W. Bush repeatedly stressed the need to “restore order” in Los Angeles following the Rodney King verdict. The rhetoric has changed little in the more than four decades since the uprisings then. In his comments outside the Rose Garden in 2015, President Barack Obama condemned those who looted businesses and caused damage in Baltimore City.

Johnson’s assumption that a sinister plot was behind the unrest in 1967 is deeply flawed because “riots” are often difficult to predict, says West. Notably, the Congressional commission that Johnson had formed in response to the first wave of demonstrations famously concluded: “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.”

“When Martin Luther King said ‘riot is the language of the unheard,’ it has a particular singularity in its distinctiveness,” West says. “That you got a lot of oppressive conditions, you got levels of social misery. And they can be in place for a while and there’s still no riot. Usually there’s a particular moment where the righteous indignation spills over because people could just no longer take it. It could be a police killing a fellow citizen, it can be an ugly act of violation of respect of somebody. It’s gotta be something that’s deeply psychic, and it touches the spirit of a people. They’ve reached a point where they actually engage in rebellion.”

One common theme of most uprisings, aside from officials downplaying them as looters run amok, is a militarized reaction by state and local governments. While police forces in tactical gear have become a common sight in modern America nowadays even during peaceful protests, the government’s mobilization of such forces has been consistent throughout decades. In response to the unrest in Baltimore, officials went as far as recruiting the U.S. Army to assist local authorities policing the streets.

The most significant difference between the riots of the ’60s and the most recent instances of social and public dissonance was the election of the nation’s first black president. Caught up in the frenzy of such a historic win, many falsely associated Obama’s rise to political prominence with the end of racism in America, and a new day for historically disenfranchised African Americans.

This was blatantly not the case, as Hamm and so many others explain.

“People [are] like, ‘Well we elected a black president so that means we’re like a pro-racial nirvana now right?’ And obviously the events of the time show us that we are far away from that,” he explains.

Even as a black man took up residence in the White House, black men were being killed at the hands of the police across the nation. Perhaps the most striking example of the deep and systemic racism is in America was the rise of Black Lives Matter, which came to be during Obama’s presidency.

“That’s indictment,” says West, bluntly. “You got a black president, black attorney general, black head of homeland security and black folk voted and supported all three of them, but the police still killing young black youth, week in and week out, and you can’t stop it other than some investigation that takes a year and so forth.”

“This is not a question of another brilliant black face in a high imperial place, this is a system’s problem,” he continues. “It’s got to do with plutocrats and military industrial complex. It’s got to do with how white supremacy is used and deployed to hide and conceal grotesque wealth inequality and domination of workers at the workplace. And the homophobia and transphobia is way up, targeting the vulnerable and targeting the poor and the politically weak in order to distract persons of dealing with some of the real sources of social misery in the world. And Obama’s neoliberal policies just ran out of gas.”

Activist Rosa Clemente, who was also the Green Party’s vice presidential candidate in 2008, tells News Beat podcast she wasn’t surprised by the outpouring of emotion within the African American community following Obama’s victory.

“That’s human,” she explains. “But after four hours, you should have been like, ‘Oh, shit, the black man’s president. White supremacy’s going to be like on fleek for now, like for real through the black man.’ “But you know, it took some people one day to get there, it took people to this day [who] are like, ‘He was the great[est]—he’s the best.’ Well yeah, I mean like, if you start comparing evil to evilness, or evil squared times two and evilness, yeah, he was better. Just like Hillary Clinton would be better than Trump. But none of this is good enough for the people, period. So, there’s no indicator, no statistic that anyone could pull up that shows a marked, material resource improvement for black people in this country, for poor people in this country, that includes black people, but poor whites, poor everybody else. Nothing materially changed. Things got worse.”

The systemic inequality and oppression faced by African Americans had deep, deep roots, continues Clemente—and as fierce as the modern-day protests blaring through our TV sets are, America has a legacy of such rebellions.

“Our level of civil disobedience is nothing compared to what we used to do…hundreds of years ago,” she says. “Whether it was on the continent, fighting back, on the slave ship, through the Middle Passage, through women throwing themselves off balconies, or committing fratricide, so their children wouldn’t have to face the horrors of being kidnapped, being enslaved. What we’re doing now is not—first, it’s not enough. It’s not organized, and it’s not—what that usually is an expression of.”

What’s also tragically crystal clear, if history is any teacher, is that no matter the historic proportions of any event—mass rebellions throughout the country or the election of the first black president—change can be stubbornly slow, or completely elusive.

Yet just as evident is that even in the darkest of times, when the chaos feels like a black hole, there’s certain moments that have the ability to serve as catalyst for something greater.

‘I AM REBELLION’

The night of the Newark rebellion was the first time Hamm could recall his family seriously discuss racism in America.

His grandfather, who served in the Army, was a child of the South. But he hated it so much, Hamm says, that he made an impassioned plea that when he died, his body not be returned to the South for burial.

As Hamm matured, so did Newark. A week after the rebellion had ended, the city played host to a Black Power conference, which was led by famed poet Amiri Baraka—a feat Hamm still has difficulties comprehending. (Baraka’s son, Ras, is the current mayor of Newark.)

The following year, in 1968, a Black Power convention came to Newark. A year after that was a black and Puerto Rican convention.

Three years after the rebellion, Ken Gibson was elected the city’s first black mayor, a pivotal moment in Newark’s turbulent history, that Hamm directly contributes to the massive uprising. Gibson’s victory came a decade after a Newark, for years a predominantly black city, elected its first black representative to the city council.

“People talk about the physical damage,” Hamm says. “Well the city ultimately recovered. Yes, it was millions of dollars, it was a lot of damage, yes. People died, yes. But the city didn’t die. And in fact the city is right now going through some people call it a renaissance, some call it a gentrification. But the city is coming back in a strong way, economically.”

Hamm himself became a vocal activist in Newark. At 17 he become the youngest person ever appointed to the Newark Board of Education. He eventually graduated from Princeton University, where he became the leading voice behind the movement to have the college divest from the South African economy during apartheid.

Although he didn’t participate in the Newark rebellion, Hamm each year holds a remembrance event dedicated to the uprising and its impact on the city.

“You have to understand how difficult it was to make that change. It’s very difficult,” he shares. “One aspect of oppression is force and repression. The state uses the police and the state troopers and whatever they have to use to maintain the status quo. But another aspect of oppression that is less discussed is the internalization of oppression by the people who are being oppressed. They internalize their oppression. So consequently, there’s a thinking that not only do you have a system of white super-ordination and black subordination, but you have an educational system and a whole ideological infrastructure—media, culture, everything—that in fact reinforces among the black subordinate group that they are in fact inferior. That they are less than. And a lot of people accept that.”

Hamm is nowhere satisfied with the steps, however small, marginalized black communities have taken since the 1960s. That’s largely a result of the very incident that inflamed tensions in Newark in 1967: the beating of Smith by the police.

“This is the situation that we’re faced with today, and this is why these struggles continue to come up,” Hamm says. “It was police brutality that triggered the rebellion of 1967. Colin Kaepernick takes a knee in protest of police brutality because police brutality continues to this day. You know, Michael Brown is killed two years ago—in the two years since Michael Brown was killed, the police have killed 2,500 people in the United States. In 2015, 1,136 people. In this year, 2017 so far, 736 people. On average a thousand people a year are killed by the police in the United States. In one year the police in the United States killed more people than the police in Great Britain killed in the 20th century. Since 1968, at least 148 or more black people are killed by the police every year in the United States. And this is why this thing keeps churning. Why the issue won’t go away.”

Hamm won’t let it go away. But even for him, there’s no way to tell when the next major uprising will take place.

“People rise up when they’ve exhausted every other form of redress,” he explains. “No one plans a rebellion. There’s no plan. There’s no group planning and executing these things. These things are spontaneous reactions to oppression. And they will continue to happen as long as people remain oppressed.”