The term “mass incarceration” has become synonymous with the United States of America, where more than 2.2 million people are behind bars.

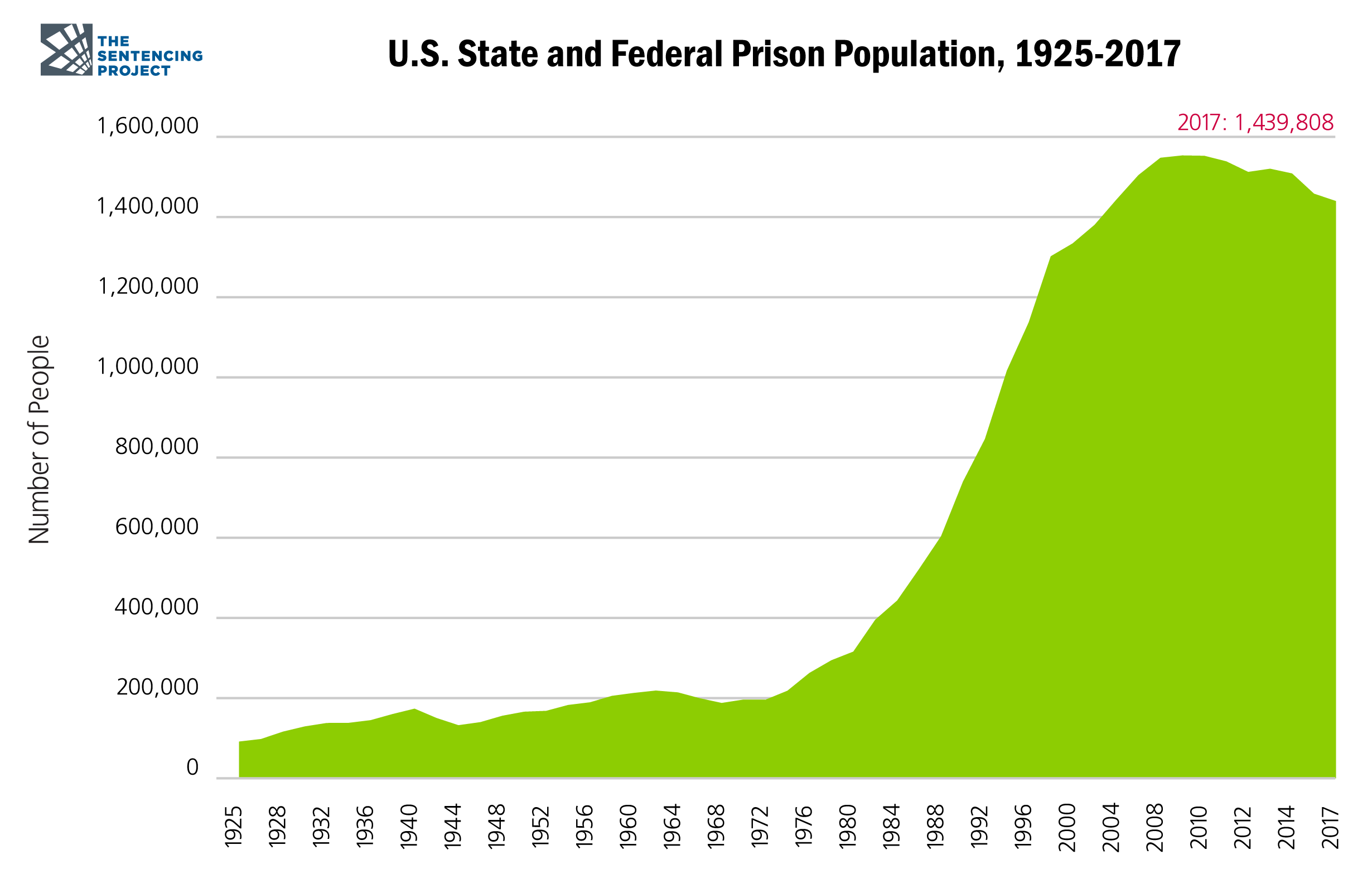

Since the 1970s, the number of people incarcerated in the country’s prisons and jails has increased by 500 percent—driven largely by the racialized war on drugs, “tough on crime” policies, and harsh sentencing laws. This ballooning of the American prison population has earned the United States the unenviable distinction of having the highest incarceration rate in the world. The phrase “Equal Justice Under the Law” may be engraved on the U.S. Supreme Court building in the nation’s capital, but the opposite is true. Black men are six times as likely to be incarcerated as their white counterparts and one-third have felony records. An additional 4.5 million people are either on parole or probation—200,000 of which are confined to electronic monitoring devices. In America, there are 10 times more people with a serious mental illness incarcerated than receiving treatment in state hospitals. To further put the scale of incarceration into perspective, consider this: The United States has 5 percent of the world’s population, but 21 percent of the prison population.

At the same time, it’s important to underscore that lawmakers and activists nationwide are advocating for solutions to reduce incarceration. Among the more popular proposals: reforms to sentencing laws for nonviolent offenses and certain misdemeanors, an end to cash bail, reforming drug laws, and investing in community-based alternatives to incarceration. Yet even such initiatives may not be enough.

“If we continue at the same pace, with the same kinds of reforms we're seeing today, the ones that people are touting as bipartisan and great, it will take us 75 years to reduce our prison population in half,” Rachel Barkow, faculty director at the Center on the Administration of Criminal Law at New York University, tells News Beat podcast.

For our part, we’ve curated a playlist of our criminal justice episodes to educate the American public about the nation’s history of incarceration. Among the topics: the racist origins of the war on drugs, cash bail, state by state disparities in compensation for those wrongfully convicted of crimes, youth prisons, prison rape and the #MeToo movement behind bars, e-carceration, prison abolition, restorative justice, and more. Download the Spotify playlist here.

The “war on drugs.” “Three strikes” laws. “Tough on crime.”

Even the most politically disengaged American has likely heard at least one of these terms. Each of these are among the leading drivers of incarceration in the United States.

As we explore the policies that contributed to mass incarceration in America, it’s also important we reckon with the country’s role in establishing a prison regime and the collateral consequences associated with imprisonment.

We know that more than 2.2 million Americans are in jail or prison in the United States—and that’s with incarceration levels leveling off after peaking in 2008. But how does a society, such as one ostensibly built on a foundation of freedom and liberty for all, appropriately quantify mass incarceration?

Do we only refer to the aforementioned 2.2 million locked up in prisons and jails across the United States? Should we include the 4.5 million additional people confined to some form of parole or probation? What of the estimated 50,000 young people in youth prisons? As we continue to discuss the role of mass incarceration in American society, how can we forget the 6.5 million people who have at least one immediate family member in jail or prison? Indeed, loved ones are free to pursue their dreams but the state of suspended animation they’re living in as they await a family member’s return may be an equally gut-wrenching experience.

And that’s not all.

A full examination of mass incarceration would be incomplete if we ignored the millions of Americans with felony records who’ve lost the right to vote. Felony disenfranchisement laws, among the last vestiges of Jim Crow, have stripped 5 million people of their ability to cast a ballot. Only two states—Maine and Vermont—allow people with felony records to vote, including those currently serving sentences.

The collateral consequences of imprisonment are similarly far-reaching.

“Collateral consequences are known to adversely affect adoptions, housing, welfare, immigration, employment, professional licensure, property rights, mobility, and other opportunities—the collective effect of which increases recidivism and undermines meaningful reentry of the convicted for a lifetime,” the American Bar Association wrote in a 2018 report, which noted that 60 percent of who leave jails or prisons remain unemployed one year after their release.

As writer, lawyer, and civil rights advocate Michelle Alexander argues in her era-defining book, “The New Jim Crow,” the result is a “racial caste system” that effectively stifles black mobility.

“What is completely missed in the rare public debates today about the plight of African Americans is that a huge percentage of them are not free to move up at all,” Alexander writes. “It is not just that they lack opportunity, attend poor schools, or are plagued by poverty. They are barred by law from doing so. And the major institutions with which they come into contact are designed to prevent their mobility. To put the matter starkly: The current system of control permanently locks a huge percentage of the African American community out of the mainstream society and economy. The system operates through our criminal justice institutions, but it functions more like a caste system than a system of crime control.”

“Like Jim Crow (and slavery),” she adds, “mass incarceration operates as a tightly networked system of laws, policies, customs, and institutions that operate collectively to ensure the subordinate status of a group defined largely by race.”

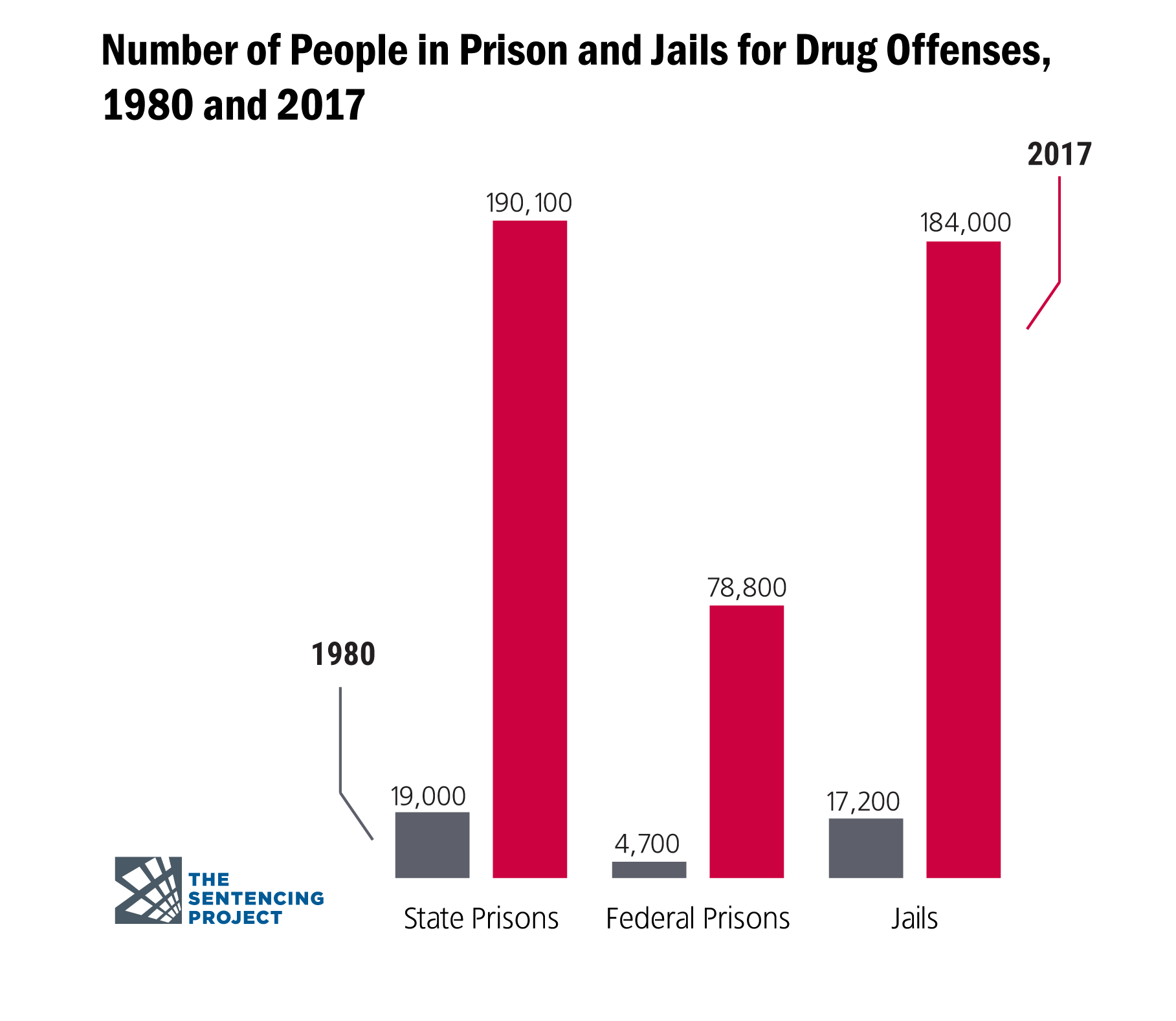

Currently, more than 400,000 people are imprisoned on drug crimes in U.S. jails and prisons, up from just 40,000 in 1980. Drug offenders, according to the Bureau of Prisons, account for more than 40 percent of the federal prison population, a third of whom received mandatory minimum sentences, among the hallmarks of the “tough-on-crime” era in American politics.

So, how did we get here? Many criminal justice experts point to the so-called “war on drugs,” including other factors, for inflating America’s jails and prisons. Presidents Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan are often credited with birthing the modern-day drug war—a nationwide crusade that has cost American taxpayers more than $1 trillion, and counting.

On June 17, 1971, Nixon declared an all-out offensive on drugs, characterizing it as “public enemy number one.” This followed a presidential campaign in which Nixon ran as the “law-and-order” candidate and reportedly gave more than a dozen speeches espousing such themes. When Reagan came into office he eagerly embraced Nixon’s war and subsequently made it his own. Reagan’s Justice Department dramatically shifted its focus from white-collar criminals to so-called “street crimes,” according to Alexander’s “The New Jim Crow.” When Reagan launched his sequel to Nixon’s drug war in October 1982, “less than 2 percent of the American public viewed drugs as the most important issue facing the nation,” Alexander reported.

“Practically overnight the budgets of the federal law enforcement agencies soared,” she wrote. “Between 1980 and 1984, FBI anti-drug funding increased from $8 million to $95 million. Department of Defense anti-drug allocations increased from $33 million in 1981 to $1,042 million in 1991. During that same period, DEA anti-drug spending grew from $86 to $1,026 million, and FBI anti-drug allocations grew from $38 to $181 million.”

Make no mistake, the drug war has been a bipartisan affair. Clinton’s 1994 crime bill created a boom in prison construction and established mandatory minimums for drug offenders. Nearly two decades after the crime bill was enacted, 36 percent of federal drug convicts received mandatory minimum sentences.

It’s also important to note that the drug war is not a modern phenomenon. It can be traced back to the era of Prohibition, and the true architect of this near-century-long anti-drug campaign was an obscure career government official who has seemingly been lost to history: Harry Anslinger. Anslinger was the first-ever commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN), the predecessor to today’s Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). He presided over the agency for 32 years, nearly as long as J. Edgar Hoover’s infamous tenure at the FBI.

As we previously reported: “It’s near-impossible to exaggerate Anslinger’s contributions to the now-global drug war. Not only did he have an oversized role in promoting and enforcing anti-drug policies and lobbying for stricter laws in the United States, Anslinger successfully strong-armed entire countries to wage this war, his way. To best illustrate Anslinger’s intimidation tactics, Mexico, for example, initially refused to comply with his demands until the United States threatened to withhold painkillers from Mexicans.”

“Every U.S. president since Harry Anslinger has fought his war,” Johann Hari, journalist, and author of “Chasing the Scream: The First and Last Days of the War on Drugs,” tells News Beat podcast. ”And so you see this with of course Nixon is a very Anslinger figure—paranoid, racist, and so on—and of course we see this with Reagan. Actually, a guy who doesn’t get enough stick for this is Bill Clinton.

“The worst person on the drug war—Nixon is a monster, Reagan is a monster—but actually, Bill Clinton is responsible for some of the worst intensifications of the drug war, some of the most racist policies; so this has been a bipartisan affair.”

Sentencing reform has emerged as a key policy initiative among lawmakers and advocates who want to reduce incarceration. That’s because prohibitively long sentences are partly to blame for the rise in incarceration, the result of people being locked up for long periods, even if the punishment seemingly doesn’t fit the crime.

Rachel Barkow, faculty director at the Center on the Administration of Criminal Law at New York University, says sentence lengths in the United States have increased in the past three decades.

“One of the big drivers of making sentences longer has been the proliferation of passing of mandatory minimums, Barkow, author of “Prisoners of Politics,” tells News Beat podcast. “So at the federal level, in lots of states, there are mandatory minimum sentences that judges have to impose, no discretion to do otherwise. And some of them are quite lengthy. They can be life sentences for things like drug offenses...There's long sentences, like multiple decades for a range of crimes, from drugs to firearms to crimes involving homicide, so it's definitely one of the big drivers.”

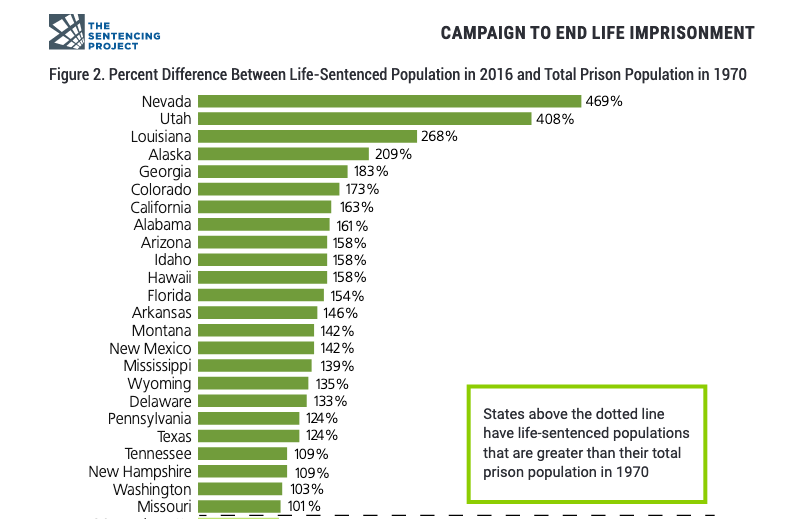

The policies that experts say have had the most significant impact on sentence lengths are mandatory minimums, three-strike laws, and truth-in-sentencing laws. Currently, one in nine people in prison is serving a life sentence, according to The Sentencing Project, a nonprofit advocating for an end to mass incarceration. The number of people relegated to life behind bars has skyrocketed from 34,000 in 1984 to more than 160,000 in 2016.

"The United States now holds an estimated 40 percent of the world population serving life imprisonment and 83 percent of those serving life without the possibility of parole," according to a new report from The Sentencing Project. "The expansion of life imprisonment has been a key component of the development of mass incarceration."

(Caption: Report from The Sentencing Project on current life-sentence populations in the United States as compared to total prison populations in 1970.)

Mandatory Minimums

Mandatory minimums effectively strip judges of discretion during sentencing and put more power in the hands of prosecutors. While such sentencing guidelines existed for decades, the practice became more common after Congress passed the 1984 Sentencing Act. The law exclusively informed federal sentencing guidelines, but individual states quickly followed suit.

As the non-partisan law and public policy think tank Brennan Center for Justice at New York University Law School states: “Simply put, anyone convicted of a crime under a ‘mandatory minimum’ gets at least that sentence. The goal of these laws when they were developed was to promote uniformity; it doesn’t matter how strict or lenient your judge is, as the law and the law alone determines the sentence you receive.”

Three-Strike Laws

Beginning in 1993, nearly two dozen states and the federal government enacted so-called “three-strike” laws that imposed life sentences on people who committed a trio of certain felony offenses, according to the nonprofit, criminal justice-oriented public policy think tank Prison Policy Initiative.

Life sentences are so pervasive that one in nine people in prison are serving a life sentence and one in seven are serving either a life sentence or a “virtual life sentence”—meaning a prison term of 50 years or more. As with other elements of the criminal justice system, there’s a substantial racial disparity in sentencing: Nearly half of those serving actual and virtual life sentences are black.

Truth-In-Sentencing Laws

When discussing incarceration in the United States, it’s important to note that the federal government generally has minimal control over policies that impact the far majority of people who are incarcerated. An estimated 90 percent of sentenced prisoners in the country are confined to state institutions. As much as some federal lawmakers like to express support for criminal justice reform, federal legislation has a marginal impact on the broader criminal justice system. The 1994 crime bill is an outlier, however, as it had far-reaching implications across the country.

The law effectively incentivized tough-on-crime policies by providing federal funding for prisons, thousands of new police officers and harsher penalties. The law enabled grants for “truth-in-sentencing” laws that mandated inmates serve a specific portion of their sentence before being eligible for release. While the federal standard was 85 percent of an individual’s sentence, the threshold varied by state. By 1997, more than half the states in the nation had passed “truth-in-sentencing” laws, totaling $234 million in grants. At the same time, 14 states abolished parole board release for all offenders beginning in the mid-'70s—just as the modern-day drug war took hold—and the end of the 20th century. These laws contributed to a 7-percent rise in state inmate populations between 1990 and 1997, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, an arm of the Department of Justice.

The bail system has come under intense scrutiny in recent years as more and more Americans confront a troubling reality: Nearly half-a-million people who haven’t been convicted of a crime are locked behind bars because, for the most part, they can’t afford their freedom.

According to current figures, 75 percent of people inside American jails haven’t been convicted of a crime, meaning more than 460,000 people are locked up awaiting trial, or more likely, accepting a guilty plea. County governments cumulatively spend around $9 billion in taxpayer dollars for pre-trial detention of legally innocent people.

Bail reform is one of the rare initiatives that enjoys relatively strong bipartisan support, as lawmakers contend with the moral and financial toll of incarcerating people accused of crimes and its disproportionate and potentially long-lasting effect on poor people. New York is the most recent state to embrace bail reform—although not without a degree of backlash—which eliminated bail in most nonviolent felony and misdemeanor cases. Before the law was passed, about 10,000 people each year in New York City were charged with a misdemeanor, with bail set at $2,000 or less—an amount they couldn’t afford. Other states to tackle bail reform include California, New Jersey, Kentucky, and Arizona. Dozens of municipalities, including many in Alabama, have reformed their practices in response to lawsuits.

“Bail is sort of the grease in the wheels of this machine that just churns out misery and incarceration,” Peter Goldberg, executive director of the nonprofit Brooklyn Community Bail Fund, tells News Beat podcast. “Because in New York, we arrest close to a quarter of a million folks for misdemeanors every year, and there’s no way that those cases can be tried in any meaningful way.”

There’s a long history in American politics of opposition to bail.

In 1964, Robert Kennedy, then the U.S. attorney general, roundly criticized the mechanism by which the country detains people before trial.

“The rich man and the poor man do not receive equal justice in our courts,” Kennedy said, “and in no area is this more evident than in the matter of bail.”

This two-tier system of justice that Kennedy was referencing is an argument critics of the system continue to make, along with highlighting bail’s residual consequences.

“The impact of being in jail is something that I think most people would understand,” Alice Fontier, managing director of the Criminal Justice Practice at The Bronx Defenders, tells News Beat podcast. “You have no access to work, your finances, money. Anything that you were doing in your life is completely stopped.”

As with anything in politics, bail reform is complicated. Consider how bail reform is playing out in California: In 2018, the state legislature voted to abolish cash bail, but ultimately alienated early supporters by amending a bill popular among reformers to include a computerized risk-assessment system that critics warn perpetuates pre-existing racial disparities. The fate of the law will be decided by California voters later this year in a statewide ballot referendum.

Elected prosecutors play a unique role in setting policies and guidelines that inform law enforcement practices, and therefore wield a great deal of power in local communities.

“They have the discretion on a daily basis to make decisions both small and large that impact the lives of tens of thousands, millions of people in this country,” Arisha Hatch, director of progressive nonprofit civil rights advocacy group Color of Change PAC, tells News Beat podcast. “Decisions like whether to charge something as a misdemeanor or a felony. Decisions about whether to charge something at all. Decisions about whether to ask for bail in a particular case. And so these tiny decisions add up and have power in people’s lives.”

At a time when one-third of the 2.2 million Americans incarcerated are black, an estimated 90 percent of prosecutors are white. In many cases, only incumbents appear on election ballots, because the majority of district attorneys run unopposed.

Miriam Krinsky, executive director of nonprofit Fair and Just Prosecution, which works with district attorneys advocating for a new approach to criminal justice, tells News Beat podcast it’s sometimes difficult for elected DAs outside of disenfranchised communities to understand the circumstances that lead to incarceration.

“You can't really understand somebody until you walk a mile in their shoes,” she says. “I think that the only way to truly understand the struggles of all parts of our community are when DAs are reflective of the rich diversity of our community. And I think it's unfortunate that the ranks of elected DAs have not in the past reflected the diversity of our community.”

“The majority of the DAs that we work with are DAs of color, many of them are women, and many of them broke through glass ceilings or beat incumbents who reflected a prior way of thinking about criminal justice issues,” Krinsky adds.

In recent years, momentum has grown behind so-called reform prosecutors with ambitious reform goals, among these: ending cash bail, decriminalizing marijuana, reducing incarceration, and investing in alternatives to incarceration, such as restorative justice (more on that in Chapter 13).

Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner, a former public defender, is perhaps the most notable reform prosecutor to hold the position. Other progressive candidates-turned-districts-attorney include Rachael Rollins in Boston, Wesley Bell in St. Louis, and, most recently, Chesa Boudin in San Francisco.

Bell’s campaign was the perfect case study in what can happen when a legitimate contender steps into a race: Bell unseated a 28-year incumbent who had only faced three challengers during his nearly three decades in office.

Boudin also confronted considerable obstacles. Throughout the campaign, he had to defend his presence in the race due to his parents’ role in a fatal armed robbery. Meanwhile, weeks before the November election, San Francisco Mayor London Breed filled the vacant position by appointing as interim district attorney Boudin’s closest challenger, Suzy Loftus, whom she had previously endorsed.

Boudin ran a victims-first campaign and promised to slowly implement restorative justice as a potential alternative to incarceration. Since taking office, he has already fulfilled one campaign pledge: eliminating bail in all circumstances.

“We know that the tough-on-crime era was a failure,” Boudin told News Beat during his campaign in 2019. “It was a failure in terms of the cost in California—10 percent of the state budget goes to the Department of Corrections, [and] that doesn't even count local policing or jails. We also know that two-thirds of the people getting out of prison will be reincarnated within a couple of years. So it's not rehabilitating. It's not breaking this cycle. And we also know that most victims are profoundly dissatisfied with the way they've been treated by the criminal justice system, and with the outcomes.”

Krinsky believes voters better understand the consequences of mass incarceration and the role DAs have played in enforcing punitive policies that have disproportionately impacted minority communities.

“We know that the ramping up of larger and larger numbers of incarceration has simply destroyed families and destroyed communities,” she says. “And that it hasn't inured to the benefit of public safety, either. We spent a lot of money on increasing the size and the reach of our incarcerated system, and I think that voter sentiment are demanding something different. And these elections are reflective of a moment in time that I think is pretty significant, in terms of voters wanting to see different individuals, different demographics, and different philosophical choices fill the role of elected DAs.”

Not only have experts linked punitive policies of the past to America’s current prison regime, but there’s also a connection to the explosion in post-release supervision. The number of people serving some form of parole or probation has quadrupled in the last 30 years—and upwards of 200,000 of these people are required to wear ankle monitors, which can either share real-time GPS data or provide a next-day downloadable report of a person’s movements.

As we’ve previously reported: “Just as the country’s incarcerated population ballooned since the 1970s, so too has the number of people in post-release and pretrial supervision, and consequently, more people than ever are under electronic monitoring (EM). This phenomenon has created a lucrative cottage industry in which companies are offering electronic monitoring devices to everyone from state correction services to federal authorities. Meanwhile, the continued blurring of the lines of state supervision and surveillance has raised privacy concerns, given the ubiquity of tracking tools already available to law enforcement in the form of license plate readers, Stingrays, and the virtual dragnet of security cameras, say prison reform and privacy advocates.”

According to racial, economic, and gender justice nonprofit MediaJustice, there’s been a 150-percent increase in the number of people on electronic monitoring. Critics of these devices argue that those wearing monitors are effectively incarcerated because they’re generally confined to their homes or a limited geographic radius.

“Is the sort of decarceration that we’re demanding a fundamental shift in how we respond to harm and maintain public safety?” Myaisha Hayes, national organizer on criminal justice and technology at MediaJustice, tells News Beat podcast. “Or is a demand to decarcerate about evolving our criminal justice system with technologies that creates digital prisons that we’re going to have to contend with years later down the line when we see a crisis happening with so many people being incarcerated in their homes by these devices?”

Between 1980 and 2015, the probation population increased from 1.1 million to 4.3 million, according to MediaJustice’s #NoMoreShacklesReport. At the same time, “conditions of supervision became much more stringent,” it noted.

A June 2019 analysis published by the national nonprofit Council of State Governments Justice Center revealed that “45 percent of state prison admissions nationwide are the result of violations of probation and parole supervision—either for new crimes or breaking supervision rules.” Of those, a quarter of all state prison admissions are blamed on technical violations, such as missing appointments with supervision officers or failing drug tests.

“On any given day, 280,000 people in prison—nearly 1 in 4—are incarcerated as a result of a supervision violation, costing states more than $9.3 billion annually,” the report states.

Another point of contention among decarceration advocates: The four largest providers of electronic monitors are private prison companies. One such firm, BI Incorporated, which is a subsidiary of GEO Group, earned nearly $84 million in revenue in 2017, MediaJustice reported.

“I think we should be concerned about location tracking,” Stephanie Lacambra, a former criminal defense attorney at digital rights nonprofit Electronic Frontier Foundation, told News Beat podcast. “Not just in the context of electronic monitoring, but in all of these other contexts as well, because I think they give law enforcement the potential to really aggregate very detailed profiles about all of us, regardless of whether you’re on probation or parole or awaiting trial.”

In July 2019, the Bureau of Justice Statistics released a startling report on sexual assaults inside various corrections institutions in the United States. Among its findings: the number of reported sexual assaults in prisons, jails, and other such facilities tripled between 2011 and 2015. The report also revealed the difficulties of investigating sexual assaults behind bars—which potentially explains why some survivors are fearful of coming forward. Of the 24,000 documented attacks, only 1,473 were substantiated. While less than 1 percent of reported assaults were proven, it represented a 63-percent increase from the 902 substantiated reports in 2011.

Sexual attacks, in general, are historically underreported, according to various studies. And experts believe there are far more of these assaults inside correctional facilities than the public hears about—partly due to fear of retaliation by both fellow inmates and guards.

“The best federal research we have indicates that over 200,000 people per year are abused inside our government institutions,” Linda McFarlane, executive director at nonprofit Just Detention International, a health and human rights organization, tells News Beat podcast, speaking of women, men, and transgender inmates.

Sexual violence, she adds, pervades every level of government-run correctional institutions, big and small.

Kids in cages.

While many Americans recoiled at the sight of migrant children in cages inside immigrant detention centers along the southern border, caging young people dates back more than 150 years, and tens of thousands of kids are currently locked up in youth prisons each day.

An estimated 50,000 young people are held in antiquated and outdated juvenile detention facilities throughout the United States, including some that were built during the Civil War.

As we’ve previously reported: “If an incarcerated youth is believed to have committed a violation, it’s not uncommon for them to be hog-tied or shoved to the ground and their faces intentionally dragged along a rug. In Miami, one facility was operating a real-life ‘Fight Club,’ in which guards instigated brawls. In one study, researchers uncovered allegations of widespread sexual abuse, with 1 in 10 youth prisoners nationwide reporting being sexually abused.”

Youth prisons cost taxpayers $5 billion annually—what many opponents consider outrageous considering nationwide recidivism rates of 75 percent.

A damning report released by the Harvard Kennedy School in 2016 examining the future of youth justice said it is “difficult to find an area of U.S. policy where the benefits and costs are more out of balance, where the evidence of failure is clearer, or where we know with more clarity what we should be doing differently.”

“This ill-conceived and outmoded approach,” the report added, “is a failure with high costs and recidivism rates and institutional conditions that are often appalling.”

As with adult prisons, there's a considerable racial disparity inside juvenile facilities: Black youth are five times more likely to be imprisoned than their white counterparts, and in some states, the rate is much higher. And even though fewer kids are being imprisoned inside juvenile facilities, the proportion of imprisoned girls is on the rise.

America’s mass incarceration crisis has also been fueled by decades-old failed mental health policies. As a result, an estimated 2 million mentally ill inmates cycle in and out of jails and prisons each year.

The crisis is so severe that there are 10 times more people with a serious mental illness incarcerated than in state treatment facilities, and the three largest jails in the country each contains more mentally ill patients than any psychiatric facility in the nation. Making matters worse, mentally ill inmates remain in jail longer than the general population, and are detained longer pre-trial.

Because of the country’s inability to adequately provide mental health care, jails have become the United States’ “de facto mental health institutions,” Leah Pope, senior research fellow at the national research and policy nonprofit Vera Institute for Justice, tells News Beat podcast.

Experts attribute this phenomenon to a period of deinstitutionalization—the idea that patients would benefit from a community-based model rather than receiving treatment inside state psychiatric facilities.

Deinstitutionalization “has been one of the most well-meaning but poorly planned social changes ever carried out in the United States,” according to a 2010 Treatment Advocacy Center study.

The nonprofit Treatment Advocacy Center’s Executive Director John Snook tells News Beat that the country did a poor job of replacing shuttered state facilities with “either community care or recognition that the illness requires something more than simply just community care.”

“In some instances, when you think about that, that makes sense,” Snook says. “Mental illness is like any other illness, sometimes you need a period of inpatient care in order to get stabilized. We didn’t provide that. And the lack of that inpatient care, combined with the lack of community care, meant that people went into the systems that couldn’t say no. And unfortunately, in most instances, what that meant is that people with mental illness ended up in jails and prisons.”

Treatment of mentally ill patients has, in some respects, come full circle. Early in the country’s history, people suffering from psychological distress were indiscriminately thrown in jails. By the early 19th century, activist Dorothea Dix helped improve treatment by advocating for asylums. About a century later, advancements in medicine helped push patients out of asylums and into federally-funded treatment centers. By the 1950s, federal lawmakers began pushing for deinstitutionalization, and the 1963 Community Mental Health Act effectively made the federal government the largest funder of mental health treatment. Only about 35,000 patients currently receive treatment at state facilities.

Snook says incarceration exacerbates mental illness, and that one way to break this vicious cycle is to expose the myth that people will receive sufficient treatment behind bars.

“We talk to jailers across the country, and families and consumers every day, and that is a myth they desperately want to break,” Snook says. “There is no worse place to provide mental wellness care than a jail. First of all, the space that we're talking about is simply not designed to provide mental health care: It's stressful, it's loud, jailers themselves are not trained to provide...the sort of treatment that a person receives.

“And then one of the big realities of incarceration,” he continues “is that there are not that many guards, [and] that as a result, there is a real focus on discipline, on following the rules. And if you have a serious mental illness, that is one of the most difficult aspects, is complying with rules...And so you basically have a situation where your serious mental illness is both causing you to be charged with even more infractions, and it's raising your profile as someone who may be assaulted either by officers themselves in some situations, or other prisoners.”

Adds Pope: “You go into any jail and you’re more likely to find someone with mental illness than you are in the community. I think the criminalization of mental illness has a lot of underpinnings.”

We’re sure you’ve read about exonerations in your local newspaper, watched a documentary, or even listened to a tragic story of a wrongful conviction on a podcast. Despite the scrutiny around wrongful convictions, it’s nearly impossible to quantify how many people currently in prison may be innocent.

So, let’s focus on what we do know. For one, exonerations have sharply increased since the late 1980s, having peaked in 2016 with 180 people nationwide having been legally proven innocent. Secondly, more than 22,000 combined years have been stolen from the more than 2,500 people who’ve been exonerated since 1989, according to the National Registry of Exonerations, a project of the University of Michigan Law School, Michigan State University College of Law, and the University of California Irvine Newkirk Center for Science and Society that compiles data related to wrongful convictions.

While various elements of the criminal justice system have their own unique qualities, one thing is consistent: racial disparities. A report from the National Registry of Exonerations found that 47 percent of exonerees as of 2016 were black, even though African Americans were only 13 percent of the U.S. population at the time. Additionally, the report noted that innocent black people are about seven times more likely to be convicted of murder than their white counterparts.

The same goes for drug crimes.

“The best national evidence on drug use shows that African Americans and whites use illegal drugs at about the same rate,” the report states. “Nonetheless, African Americans are about five times as likely to go to prison for drug possession as whites—and judging from exonerations, innocent black people are about 12 times more likely to be convicted of drug crimes than innocent white people.”

As we’ve previously reported, securing an exoneration is only part of the battle since “only 3[5] states [and the District of Columbia] in the United States have exoneration compensation statutes on the books for people who were wrongfully convicted. In some instances, the laws fail to offer proportionate compensation to exonerees in relation to how many years they lost behind bars.”

So how does an exoneree receive compensation? Well, there are various mechanisms by which they can be compensated for the time spent behind bars, including state statutes, lawsuits, or so-called “private bills” issued by a state legislature. As for state laws, some are more generous than others. According to the National Registry of Exonerations, as of 2016, 523 people were awarded compensation through state statutes, totaling $400 million.

Rebecca Brown, policy director at the nonprofit Innocence Project, which advocates for people falsely accused of crimes, tells News Beat podcast that the majority of compensation laws are “woefully inadequate.” Advocates for more robust statutes argue that current laws don’t provide proportionate compensation for the time they served, and contain loopholes that deny funds to those who pleaded guilty or who have a previous felony conviction unrelated to their exoneration case.

Here’s more from our episode on exoneration compensation laws:

“In New York, for example, the wrongfully convicted—in some cases, people who were locked away before the first iPhone was released, and with little or no basic understanding of law or statutes ostensibly created to assist them following exoneration—are expected to sue the government for damages. Other states cap the amount a person can receive over their lifetime, while others insert legal caveats that make it almost impossible to receive compensation. A wrongfully convicted person in New Jersey who pleaded guilty to the crime in which they were convicted, for instance, is not entitled to any monetary award.”

In an era in which people are fighting hard for even minor criminal justice reforms, the idea of abolishing prisons would seem a radical concept. The truth is that the prison abolition movement found its way into the mainstream when prison populations were relatively modest by today’s standards and before the prison industrial complex fully took hold of American society.

According to experts interviewed by News Beat, academics and lawmakers alike began to consider a nation without jails or prisons in the 1960s and early 1970s.

“People really believed that that was possible,” Mariame Kaba, a prison abolitionist and founder of nonprofit Project NIA, which explores alternatives to juvenile incarceration, tells News Beat podcast. “We had less than 300,000 people in 1970 in both our jails and prisons...So you can imagine at that time people could imagine that there was a way to actually end the institution of incarceration because we had a relatively smaller group of people that were actually involved in the system.”

But the preceding years changed everything, as the war on drugs took center stage—bookended by the Nixon and Clinton administrations—and more punitive policies were adopted.

While it's been largely erased from wider discussions about carceral institutions, the abolition movement remains very much active. Among those to carry on the legacy: such groups and figures as California-based nonprofit Critical Resistance, as well as activists Angela Davis and Ruth Wilson Gilmore.

“In the 1970s, the United States' prison population was a little over 100,000 people in prison and jail,” Joshua Dubler, an assistant professor of religion at the University of Rochester, tells News Beat podcast. “And there was a gathering sense in many sectors of the society, both at the grassroots and elite levels, that the prison was a bad institution, a hurtful institution that wasn't following through on its promise of rehabilitating individuals and that we should get rid of it.”

Abolitionists view mass incarceration through a wide lens. Not only do they take into account millions who are currently incarcerated, but they consider the 12 million who cycle in and out of jail each year, policing of minority communities, surveillance, lack of housing, struggling schools and myriad socioeconomic obstacles people have to face.

Criminal justice reform has vaulted to the top of the legislative agenda in many states across the country, due to the burden the system puts on state finances, and as Americans come to grips with the moral cost of jailing millions of people, including a disproportionate number of minorities.

In 2019, several states sought to tackle the prison crisis through sentencing reform, by decriminalizing marijuana, or through other measures that would limit the impact of collateral consequences of those who’ve been justice-involved. Congress also took action with the passage of a bipartisan law called the First Step Act, which makes it easier for federal inmates to receive early release.

As we’ve discussed, the war on drugs played a pivotal role in fueling mass incarceration in the United States. At least 15 states have tried to reduce the chances of someone landing in jail or prison due to a drug infraction by decriminalizing marijuana. Eleven states have opted to legalize marijuana and in some cases expunge the records of those with previous marijuana convictions. Along with legalizing marijuana, Illinois last year passed a law that could potentially expunge the records of more than 700,000 people with certain marijuana convictions.

Despite their best efforts, lawmakers are cognizant that criminal justice reform is a marathon—and one that could be upended at any time.

“The criminal justice system is huge, it’s a juggernaut,” Pennsylvania State Rep. Jordan Harris, a Democrat, told News Beat podcast last year. Harris helped found the Criminal Justice Caucus and has teamed up with his Republican colleagues to produce reform legislation. While the U.S. prison population grew 600 percent between 1973 and 2009, Pennsylvania’s increased 850 percent, underscoring the difficulties of dramatically reducing jail and prison populations.

The Sentencing Project has said that at the country’s current pace it will take at least 75 years to reduce the prison population in half.

“[T]he overall impact of reforms has been quite modest,” the organization noted. “With 1.5 million people in prison in 2016, the prison population remains larger than the total population of 11 states. If states and the federal government maintain their recent pace of decarceration, it will take 75 years—until 2093—to cut the U.S. prison population by 50 percent. Expediting the end of mass incarceration will require accelerating the end of the Drug War and scaling back sentences for serious crimes.”

California has been among the leaders of criminal justice reform after the U.S. Supreme Court mandated it substantially reduce prison overcrowding a decade ago. After voters approved a reform measure dubbed “realignment” in 2011, its state prison population fell 25 percent by 2016.

As we reported in a special collaborative episode with nonprofit news organization The Marshall Project, the state has passed a variety of reforms through the years:

“Beyond addressing its once-infamous overcrowding problem, the state has adopted a medley of new reform-inspired laws: Prop 47 in 2014, which reduced sentences for low-level drug and property crimes; Prop 57 in 2016, which expanded parole eligibility for non-violent criminals; SB 1437, which effectively eliminated the so-called ‘felony murder rule;’ and others.”

“California looks a lot like the nation,” Mia Bird, research fellow at the nonprofit think tank Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC), told News Beat podcast. “And so there’s a lot to be learned from the California experience, but I certainly think across the country, you know, California may have been a bit on the leading edge because of circumstances and prison overcrowding, but across the country these are conversations that are being had and there’s legislation moving forward just to try to make the criminal justice system more cost-effective and more equitable.”

Meanwhile, grassroots organizations and myriad other like-minded groups nationwide are doing their part to generate enthusiasm around criminal justice reform. The nonprofit American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), for example, through its Smart Justice Campaign, announced a 50-state blueprint to cut incarceration in half.

“What we realized early in this campaign is that no organization, including the ACLU, had really done the state-by-state research to figure out how we [cut incarceration in half],” Janos Marton, a candidate for Manhattan district attorney and a former state campaign manager for the ACLU Smart Justice Campaign, told News Beat podcast.

“Surely we all know the broad parameters, is that we all believe that there should be far fewer people in jail, pretrial, especially people held on cash bail,” he continued. “We agree that sentences are too long and parole is too punitive. But what are the hard numbers for things that we would need to change in order to get to 50 percent? So the blueprint project is both a national and a state attempt to do that. It goes on a state-by-state basis, talking about which laws are the drivers of mass incarceration. And it actually has a tool where you can personally see how to change existing laws to reduce the jail and prison population in the long term.”

While legal scholars and reform advocates are embracing this era of change, some point to the number of people incarcerated for violent crimes as a deterrent to decarceration. Violent crimes currently account for more than half of state prison populations.

“If more than half of those folks are in there for some kind of crime that involves violence, then serious reform requires us to think about what to do with that population, and to think about how we want to approach and tackle those issues,” Barkow of NYU tells News Beat podcast.

As we’ve just discussed, fundamentally reforming the criminal justice system is no small task. That’s partly due to decades of “tough on crime” policies that have become part of the fabric of American politics and culture.

As advocates demand sweeping changes, some are looking toward restorative justice as a potential alternative to incarceration because of its victims-first approach. If a victim of a crime gives their blessing, defendants bypass the courts altogether, and instead communicate directly with the person they harmed, during various supervised sessions.

Proponents of this approach argue that it’s far more effective than courts, because defendants actually have to confront the person they harmed and reconcile with the fact that they did something wrong—potentially healing wounds in a way that the traditional court process is fundamentally unable to do.

“We have this myth as a country that we’ve done mass incarceration in crime victims' names,” Danielle Sered, executive director of the Brooklyn-based nonprofit Common Justice tells News Beat podcast. “It is true that politicians have invoked crime victims, in almost all of their efforts to impose draconian sentences, whether that’s an individual case or as a matter of policy.

“It is true that some crime victims have asked for those draconian sentences,” she continues. “Those kinds of victims are actually, for the most part, the outliers. In some ways, I think the most interesting thing we’ve learned at Common Justice is about what crime survivors want.”

Common Justice distinguishes itself from similar programs by addressing crimes of serious violence—crimes that, as we mentioned, are responsible for the majority of state prison sentences.

San Francisco District Attorney Chesa Boudin centered his 2019 campaign on restorative justice, which he said helped him cope with his parents’ incarceration.

“Restorative justice is a key part of that, because it puts victims first,” Boudin says of overhauling the city’s criminal justice system. “It's not about just letting people who cause harm off without consequences, it's about recognizing that there's an intersection between accountability and healing, which our traditional, narrow focus on punishment, misses entirely.”

No spam here! Get notified when our next episode drops.